The alleged human rights abuses in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of China led to US sanctions and then the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act. The US Congress passed this Act in December 2021, and it came into effect in June 2022. However, already in 2021 the US Customs and Border Protection issued a Withhold Release Order that blocked all imports from the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps, which produces one-third of the cotton in China, and China is the second largest cotton grower after India. This blog discusses how the recent rise of economic sanctions against China, which are mainly targeted to specific locations, cause side effects along the wider supply chains. In particular, it shows how Sri Lanka’s apparel export industry was affected by the withdrawal of investment and closure of apparel factories by a Hong Kong firm hit with US sanctions.

Esquel Group and Polytex Garments Limited Sri Lanka

Polytex Garments Limited is a subsidiary of the Esquel Group, a textile and apparel manufacturer based in Hong Kong, China. Esquel is one of the largest woven shirt makers globally. Esquel acquired Polytex Garments Limited in 1983, soon after Sri Lanka opened its markets and was integrated into global apparel production networks. From a single factory building in 1983, Polytex grew into five large-scale factories by 2020. It employed around 7,000 apparel workers in total.

A family-owned business, Esquel Group was founded in 1978 soon after the Chinese Economic Reforms (also known as the Chinese Economic Miracle and ‘Reform and Opening’ up). Because Esquel is heavily invested in the Xinjiang region, it cannot simply ‘de-risk’ from China, as other textile and apparel companies have started to do by sourcing cotton fabrics elsewhere. From cotton seeds research to product retailing, Esquel has become a total service and solution provider of textiles and apparel. Esquel operates cotton ginning and spinning factories in Xinjiang, including a highly automated spinning mill with only about 45 staff controlling the 30,000 spindles. It has textile mills in Gaoming in Southern China producing mostly woven fabric, and garment factory clusters across Southern China. Esquel’s business strategy of full integration focused on one product segment, its ‘China only’ approach, and its high capital investments in spinning mills in Xinjiang make it difficult for the company to divest from its factories in Xinjiang. Esquel used to have a joint venture with the Chinese state-owned Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps to attain high-quality raw cotton, but it was divested from cotton farming in April 2020. Notably, Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps was a target of US sanctions announced in July 2020.

U.S. Sanctions and the Esquel Group

In July 2020, the USA Department of Commerce placed the Esquel Group on the Bureau of Industry and Security’s Entity List, which is a trade restriction list banning cotton and cotton products originating from the Xinjiang region in China. The ban aimed at pressuring the Chinese government over the alleged forced labour of the minority Uyghur Muslims in Xinjiang. This put onus on importing companies to ensure that none of their goods are even partially made in the region of Xinjiang. Companies on the Entity List are subject to U.S. license requirements for the export or transfer of specified items. In July 2021, Esquel filed a lawsuit seeking removal from the Entity List in the United States District Court for the District of Columbia against the U.S. government. In August 2021, Esquel was removed, with conditions, from the Entity List by the inter-agency End-User Review Committee. It is not clear what those conditions were, as they were not made public knowledge. Several weeks later, Esquel resumed its lawsuit after failing to reach an agreement with the U.S. Commerce Department regarding the timetable for removal and the specifics of the conditions for removal.

In July 2022, Ecotextile news reported that Esquel Group had suffered another setback in its appeal to overturn US sanctions against its spinning mill in China’s Xinjiang region over alleged links to forced labour. The US Court of Appeals denied the appeal limiting Esquel’s access to US markets and goods. Consequently, as reported by the Clean Clothes Campaign in 2022, international clothing brands have been ending their business relationship with Esquel in Sri Lanka since 2020. This has forced Polytex Garments to do subcontracting work for local manufacturers.

The claim of forced Uyghur labour is strongly denied by the Esquel Group. As quoted on their website “The decision to add Changi Esquel Textile Co. Ltd. to the Uyghur Forced Labour Prevention Act (UFLPA) Entity List is both misguided and unjust. We morally oppose the use of forced labour, which is completely contrary to our principles and the business practices by which we have operated for more than 40 years”. Esquel claims that it has provided extensive information about its operations, independent third-party audits, traceability documentation, supply chain maps, and a variety of other documents to the U.S. Department of Commerce and other relevant agencies “proving Esquel does not use forced or coerced labour”. Esquel claims that rather than addressing any of the facts they provided, the US government has chosen to continue to rely on a handful of misleading anecdotal media mentions and “poorly researched reports to justify its policy decisions”. On their website, Esquel claimed that they had to close several of their factories in various countries due to US sanctions. Esquel accuses the U.S. government’s “perfunctory fact-finding process has negatively affected thousands of innocent workers globally from Sri Lanka to Mauritius to Malaysia – whose livelihoods have been destroyed…” (Esquel Group; 20 June 2022).

Polytex Garments Limited in Sri Lanka – Messy closure and contested labour politics

Esquel Group declared the Polytex factory closure in Sri Lanka as a direct result of US sanctions, a fact confirmed by trade unions and employers’ associations in Sri Lanka. As Esquel Group itself reported to JustStyle, it has cut production in Sri Lanka due to “the loss of many US customers”.

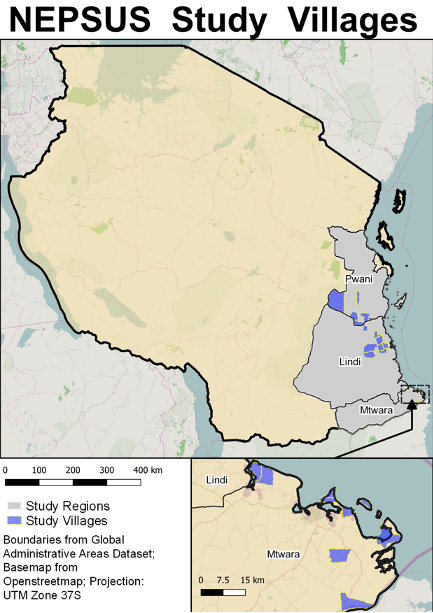

The five factories of Polytex Garments Limited were located in Ekala, Kegalle, Koggala, and Yakkala, all out of Colombo. The first to close was the factory in Yakkala in 2020. According to a trade union, the reason for the closure of the first factory was cited as lack of orders and challenges faced due to the Covid19 pandemic. Most workers were given termination benefits, with the rest transferred to the Polytex factory in Ekala, closer to the Katunayake Free Trade Zone. Trade unions said that to facilitate this transfer, the Ekala factory had to fire all or most of the workers on probation, whose employment with the factory was less than six months. This fact however is not verified by the employers. Following this, the Ekala and Kagalle factories were closed in June 2022. As reported by JustStyle, the remaining two factories – Koggala 1 and Koggala 2 were closed in March 2023. For the latter two, permission from the Commissioner General of Labour to terminate the workers’ contract was still pending as of April 2023. As confirmed by unions and workers, Polytex Garments Limited had paid over and above the legally stipulated termination benefits including gratuity, employers provident fund, compensation payment according to the termination laws, and an additional three months’ salary. Polytex also waived off all outstanding loans taken by the workers.

The events leading to the factory closures turned out to be messy and were highly contested by trade unions, workers, and employers. This was well reflected in the contrasting accounts shared by different stakeholders with regard to the closure of the Koggala factories. In spite of having spoken to multiple stakeholders – including workers, employers’ associations, trade unions, the labour department, and civil societies – it was difficult to have a clear understanding of exactly what happened during the closure of the last two factories in Koggala.

According to the representatives of employers’ associations and the labour department, before the factory closure, Polytex sought to change the name of the company from Esquel to ‘JK Apparel Koggala Private Limited’ and continue operating in Sri Lanka. The reason for the name change as revealed by the employers association was to secure the orders and independently get the quotas required for direct manufacturing instead of subcontracting through other manufacturers. This name change was thus projected by the employers association as a strategic move by Polytex Sri Lanka to distance itself from the US sanctions on Esquel. The main national trade union (Union) involved in the negotiation initially agreed to this. Workers were provided the assurance that the status and terms of employment would remain the same including salaries, job descriptions, promotion schemes, and accumulated gratuity and statutory benefits. Workers consented to this transfer in front of the Commissioner of Labour. The proceedings were discussed through a series of online meetings (due to the pandemic conditions) which were attended by all parties concerned including workers’ representatives, the labour department, employers’ representatives, and the management of Polytex.

Employers’ associations alleged that the leader of the Union then “changed his word”. Instead, the Union had demanded that Polytex terminates the contract with workers, pay compensation and termination benefits plus an additional 20% to the workers. Upon paying these benefits, the Union had requested Polytex to re-hire the workers to the ‘new company’. As the employers’ association justified, Polytex Garments Limited could not afford to pay both the termination benefits and then continue the business with the new company, especially, as they were already financially hit by the pandemic and the US Sanctions. This resulted in the closure of the factories.

The Union however shared a different version of the events that lead to the closure. According to the Union, the name change was already carried out by Polytex Koggala in 2022 and workers stayed on as employees for about one month after the name change. As a former worker of Polytex quoted “they explained to us that they could not get orders from America. They said they are changing the name to see if they could get orders”. But the Union said that they suspected that the two factories in Polytex Koggala were being sold to a financially non-viable businessman. The Union feared that a few months after the acquisition, the new buyer would go bankrupt, resulting in workers losing all accumulated benefits and compensation including gratuity and termination benefits. The Union cited this as their reason for the objections to the transfer of workers to the new factory. Subsequently, the unions advised workers not to agree to the transfer, resulting in the closure of the two factories in Koggala.

Implications for apparel workers

Indeed, Polytex workers were extremely disappointed and distressed about the factory closer. As a worker quoted “We tried very hard to stop the closure. We even met government ministers and the Board of Investment. We appealed to them to help the factory get orders”. Simultaneously many protests were being carried out by workers outside the Polytex factories reportedly against the closure of the factories. Some of these protests culminated in workers holding the General Manager and the Human Resources Manager of Polytex Garments Limited hostages on the factory premises. The two executives were rescued by army and police officers who arrived at the scene in the early hours of the following day.

The closure of Polytex Garments Limited resulted in about 7,000 job losses. At the time of writing, most of the workers who lost their jobs were unemployed. Some had gone back to their villages, and some were engaging in informal work. Some workers were hired by other factories, but many of them were again let go of when those factories started downsising due to the challenges of the economic crisis in Sri Lanka and the lack of orders. As per the labour laws, employers are able to let go of workers who are on probation (under six months of service). This unfortunately has been the case for Polytex workers who joined other factories. Another segment of workers was reported to be ‘blacklisted’ in the industry. According to trade unions, these were the office bearers and key members of the Polytex trade union, who were involved in the protests. A manufacturers association commented these were the workers who obstructed the proceedings and prevented the continuation of the business and the potential continuation of employment for workers. In addition, as confirmed by an employers association, compensation of 200 workers was pending as of June 2023 due to these workers having taken legal action against Polytex.

The closure of Polytex factories took place just as the country was emerging from the pandemic. The closure also happened in the middle of the worst economic crisis the country faced since its independence from the British Empire 70 years ago. The inflation had skyrocketed with cost of living increasing by 200% or more. At the time of the closure, garment workers were facing a rapid rise of the cost of essential goods, shortages of electricity, shortages of food, medicine, and other necessities, and a declining value of the national currency. Loss of employment in this current economic crisis had plunged Polytex workers out of the frying pan into the fire. According to the Union, two workers have already committed suicide due to the loss of income. This information however is not verified and nor published elsewhere.

Trade sanctions and increased vulnerabilities of disadvantaged communities

Sanctions are increasingly becoming the weapon of choice to enforce US foreign policy goals, from countering terrorism, battling drug trafficking, to countering human rights violations. In a fully integrated global economy however, the effects of such sanctions are not limited to the targeted countries, individuals, or governments. More often than not, the worst affected groups of such sanctions are people who already live under precarious conditions. Ironically, in cases such as of the current example, trade sanctions imposed to prevent alleged violations of human rights in one country have resulted in erosion of livelihoods and social welfare standards in another.

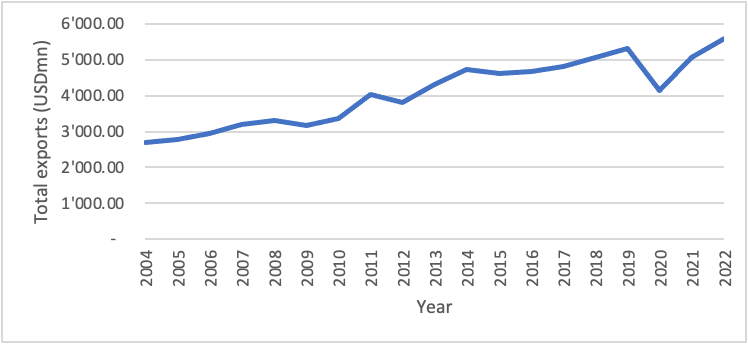

The trickle-down effects of trade sanctions in global supply chains are thus varied and complex. It is important to have a clear understanding of the costs and benefits of unilateral economic sanctions, not just for the nations such sanctions are enforced on, but also on the economies and people, who are inter-linked and integrated into these supply chains and are at the risk of being affected by such sanctions. The effects of such sanctions linger long after they are lifted because it is hard to recover from the loss of business and livelihoods. Businesses lost today for the Sri Lankan apparel industry due to the closure of five large scale factories means lower exports revenue at a time when the country is devastated by an economic crisis. Income lost today means thousands of workers are plunged below the poverty line, unable to provide for their families and growing children. Such losses – both human and economic – are difficult to reverse. While it is not clear whether the sanctions will have the intended effects on forced labour in the Xinjiang region, the sanctions have had unintended effects on the lives of labour along the apparel global supply chain as shown with the closure of Polytex Garments Limited in Sri Lanka.

Shyamain Wickramasingha is a Research Fellow at the University of Sussex Business School, and a Visiting Fellow at CBDS, within the Department of Management, Society and Communication at Copenhagen Business School. Her work focuses on the political economy of global production networks with an emphasis on inter-firm relations, uneven development, and labour regimes.