The textile and apparel industry is a globalised industry characterised by a high degree of dependency and fragmentation in global supply chains. From the mid-20th century, cotton textile and apparel manufacturing production relocated from industrialised to developing countries, particularly in Asia, and was quickly followed by the emergence of the petrochemical industry and synthetic fibre production in East Asian countries, while South Asia continued to focus on cotton and natural fibres. Changes in international trade over the past 30 years fostered the textile and apparel global value chain dynamic. These changes were marked by opening trade borders, lowering tariffs, tax breaks or subsidies offered by various governments, and free trade agreements. Low labour costs and lower production costs have shaped the decisions of global actors to relocate their operations from one country to another.

Current global trends are set to transform the global value chains of textiles and apparel again. These trends include (1)increasing production costs in China, (2) the drive to shorten supply chains post-Covid pandemic through nearshoring and seeking countries with yarn-to-garment (or vertical) production capabilities, and (3) the sustainability shift. These trends are leading global apparel buyers to diversify their sourcing away from China and Asia more generally and to consider new supply bases.

Global apparel buyers are no longer concerned only with cost, quality and speed to market when making sourcing decisions. They now must balance those criteria with sustainability goals. The climate crisis and the high contribution of the global fashion industry to greenhouse gas emissions are putting pressure on industry players to make radical changes in production processes. While consumers are increasingly demanding sustainability, the greatest pressure is coming from European country governments and the European Union Commission. Notably, existing and expected EU regulations have increased market demand for alternative sustainable fibres and textile production technologies.

As a result, new fibre and recycling technologies are in a phase of fast innovation to produce more sustainable and circular man-made fibres. The raw material for clothing production will become manufactured fibres that rely on advancements in chemical technologies and biofabrication. Virgin cotton will be of less importance, as it is replaced by natural fibres that are less resource intensive and by man-made cellulosic fibres that feel like cotton. In the transition stage, cotton will move to organic and regenerative as well as become blended with other natural and man-made cellulosic fibres. Future fibres will have a high technology content and require licensing technology, both man-made cellulosic fibres and the new wave of synthetics that seek to replace polymers.

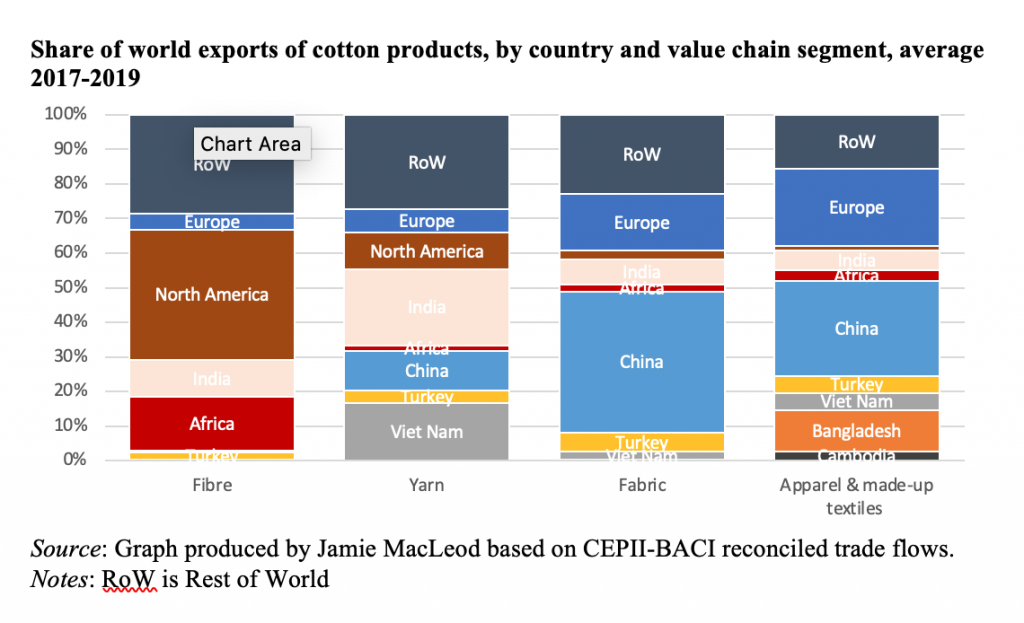

Currently, African countries export very little of what is traded within apparel global supply chains and across the African continent, except in the case of cotton, but import a large amount of what the rest of the world produces. Africa’s fabric and apparel production is biased towards cotton, especially in yarn and fabric production, with little participation in production and export of man-made fiber, yarn and fabric. Most apparel exports from the continent come from North Africa, followed far behind by East and Southern Africa. Apparel exports from the African continent go largely to Europe and then North America.

Productive capabilities in the sector in Africa remain low as the continent is largely a net importer of textile and apparel products. A couple of African countries have developed industrial capabilities in textiles and apparel, but most of it has been in the apparel segment and relies heavily on imported fabrics from Asian countries. A significant share of African apparel exports comes from North Africa, followed far behind by East and Southern Africa. West and Central African countries do not have significant apparel exports, and West Africa predominantly exports cotton fibres.

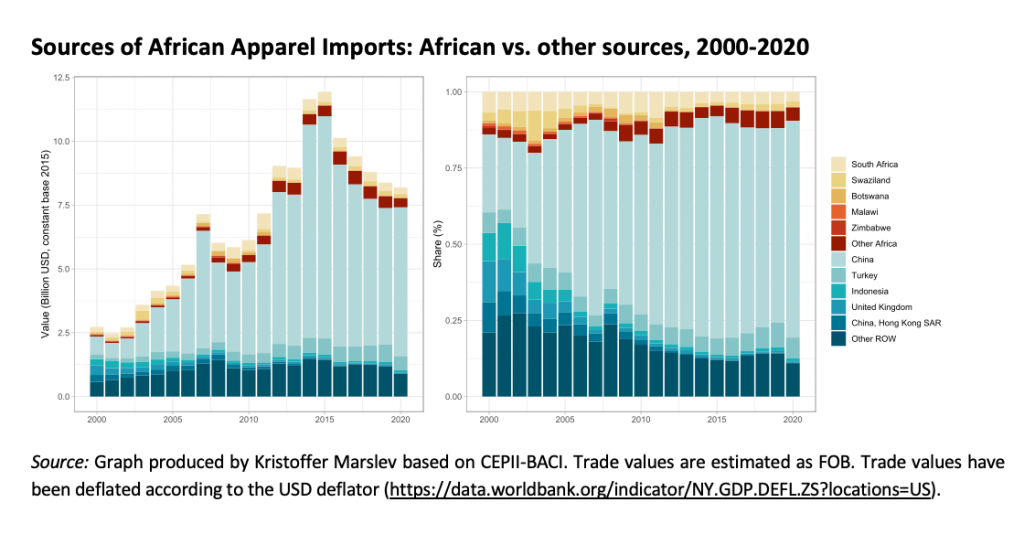

Most apparel imports on the continent come from China. Chinese imports have largely displaced imports from other Asian countries and the rest of the world but have not substantially displaced intra-African trade, which was already small in 2000 but has shrunk even further. Currently, only 8% of Africa’s textile and apparel imports are supplied by other African suppliers.

African countries have the opportunity to build sustainable textile and apparel industries from the start, which can give them a competitive advantage. The cost of renewable energy technology is falling and renewable energy technologies to power industries are evolving. New fibre and recycling technologies also offer a window of opportunity to leapfrog into the next generation of technologies. Taking advantage of this window of opportunity requires that African governments look forward and not backward, that they think in terms of building new and not rebuilding the existing textile industries.

African textile and apparel domestic and regional value chains should be based on mastering the next generation of fibre production and recycling technologies. Such a strategy involves taking risks to invest in building the knowledge and skills required for this new technology, but not taking risks will mean that African countries miss the opportunity to move to the technological frontier. Furthermore, African countries can go beyond becoming competitive in the new textile and apparel global supply chains but also use them to drive broader green industrialization processes.

Such a strategy also involves building diversified regional textile bases as well as regional value chains, which can harness the efforts of more economies and larger market demand as well as create a stronger platform of capabilities with which to engage in global export markets. A diversified regional textile base would make it easier for locally owned apparel firms to emerge and provide the opportunity to move into higher value products as well as move into design of fabrics.

The capital requirements of establishing textile mills and vertically integrated factories from spinning to fabric to garment are very high, and there is limited knowledge in most African countries on how to operate the most modern textile equipment and produce export-quality fabric. Therefore, the first wave of new investments to create a textile base will have to be led by foreign investment. Industrial policy should not be just about attracting foreign investment by providing what they want but also attracting the kind of foreign direct investment that can build globally competitive textile and apparel industries. For example, the Togolese government has started implementing its strategy centres on an eco-industrial park (PIA) with vertically integrated knit factories established through a public-private partnership with Arise Integrated Industrial Platform.

But foreign investment must lead to technology transfer in the form of skilled textile technicians and managers as well as the business acumen side of organising and managing textile and apparel firms. A key part of the industrial policy approach should include assisting local firms in leveraging technology from these foreign firms. Technology is not actually ‘transferred’ but rather must be ‘leveraged’, and to do so; local firms must build their capabilities. The actual process of technology leverage takes place through various forms of investments and contractual relations between foreign and local firms.

For more information and analysis of African textile and apparel industries, industrial policy, and implications for on-going negotiations in the African Continental Free Trade Area, see:

Lindsay Whitfield, “Current Capabilities and Future Potential of African Textile and Apparel Value Chains: Focus on West Africa, CBDS Working Paper 2022/3, Centre for Business and Development Studies, Copenhagen Business School.