Tobias Wuttke and Lindsay Whitfield

When trying to come up with lessons for developing countries that want to industrialize today, people usually refer back to the success of East Asia. But 40 years have passed since South Korea and Taiwan industrialized through exporting and import substitution. Countries trying to industrialize today face a world of globally fragmented production, a world of global value chains (GVCs). The question that has come to the forefront both in academic discussions as well as in policy circles is whether GVC participation can deliver for low-income countries what exporting did for South Korea and Taiwan. South Africa’s integration into the automotive GVC over the past 25 years makes for an interesting case study to shed some light on this question. The development of the South African auto industry has been a story of success and failure at the same time, not least because of the difficulties associated with industrializing in a world of GVCs.

South Africa is the only country in Africa, next to Morocco, that has an automotive industry worth speaking of. It produces 600,000 cars per year, 70% of which are exported, 3 out of 4 of them to Europe. The South African Department of Trade, Industry, and Competition consistently implemented an automotive industrial policy that provided investment support to the foreign-owned automotive assemblers and later support to foreign and locally owned component manufacturers as well. These industrial policies made support for foreign direct investment in the sector conditional on auto assemblers exporting cars and on using some degree of local content.

On the surface, the South African government seems to have followed the industrial policy playbook of the developmental states of the second half of the 20th Century, as illustrated by Alice Amsden. However, the automotive industry has failed to play the role of a leading sector for economic development that it did in South Korea and Taiwan. This is because South Africa’s industry lacks locally owned firms participating at the technological frontier in the industry and it lacks significant linkages with other industries in the country. These limitations result from insufficient industrial policy to support local firms and from the ways in which the automotive global value chain has evolved since the 1990s.

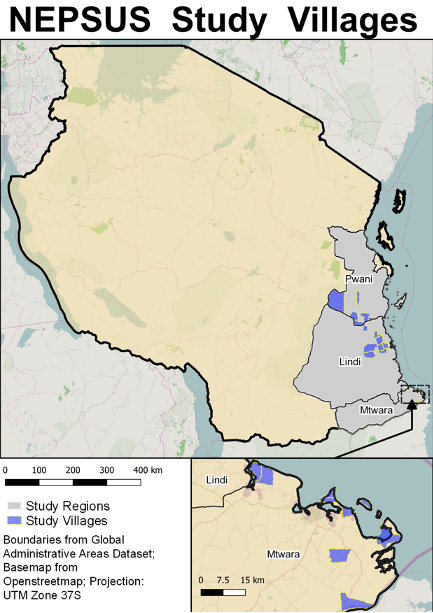

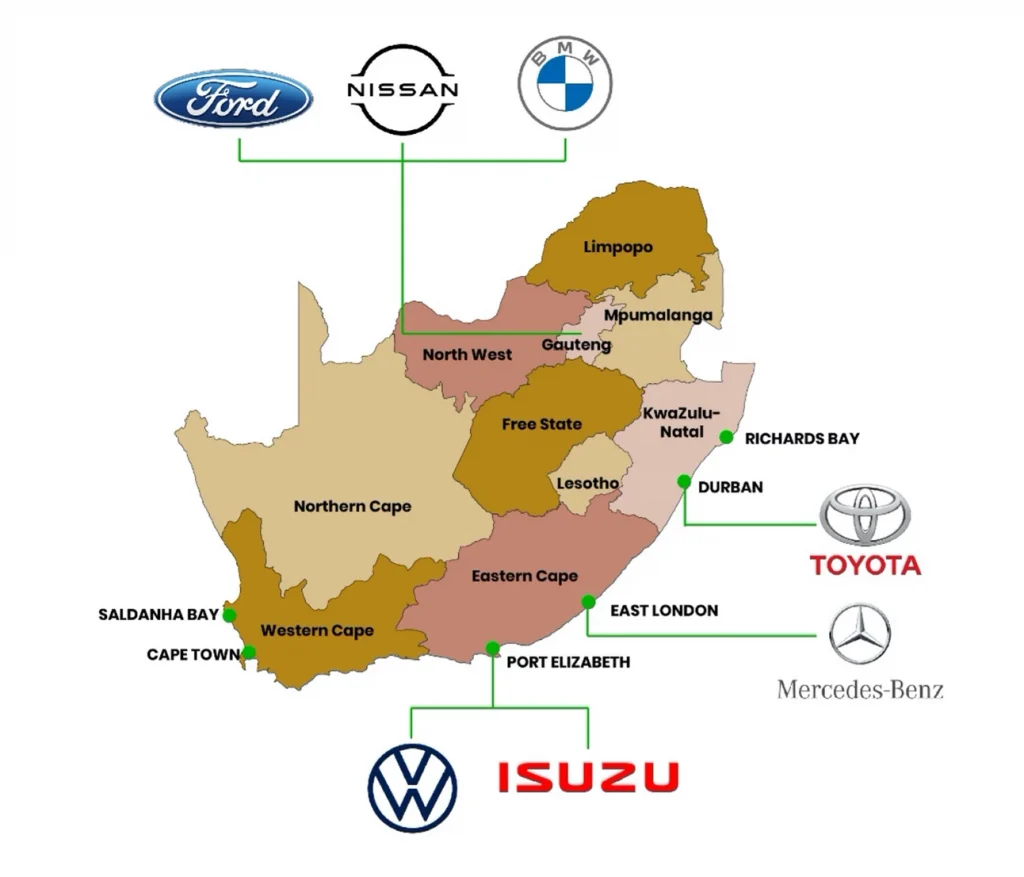

The automotive industry in South Africa makes up 6-7% of the country’s GDP, roughly a quarter of manufacturing output, and employs more than 100,000 people in vehicle and component production. There are three automotive hubs in the country: Gauteng with Ford, Nissan and BMW; the Eastern Cape with VW, Mercedes-Benz and Isuzu; and Durban with Toyota. In addition to the assemblers, South Africa has attracted investment by many of the largest multinational component suppliers, such as Continental, ZF, Bosch, MA Automotive, Dana Spicer, Benteler, etc. There are also around 200 locally owned component manufacturing firms engaged in the automotive value chain.

The automotive industry has lots of potential for backward linkages. A car is made of 10,000 different parts, from various materials – steel, aluminium, plastics, glass, leather, textiles, rubber. Automotive production is characterized by just-in-time (JIT) and just-in-sequence (JIS) requirements, which means that some local footprint is always established once volumes go beyond pure kit assembly. But on the other hand, the automotive GVC is also characterized by follow design and follow sourcing, meaning, for example, that Volkswagen designs their car in Wolfsburg, produces that exact car in its plants all over the world without much local design adaptation, and asks its established large suppliers from developed countries to set up subsidiaries next to its plants in developing country locations to fulfil the JIT and JIS requirements.

This used to be different. Up to the late 1980s, cars were locally designed, and significant and distinct local supplier networks supplied materials and parts to the automotive assemblers in developing countries. This situation has been superseded by the almost total ubiquity of the ‘global car’, with follow design and follow sourcing, since the 1990s. In the case of South Africa, in the early 1990s, several of the assemblers and most of the component firms were partially or fully locally owned. This had already changed by the mid-2000s with all seven assemblers as well as many of the component firms being in full foreign ownership.

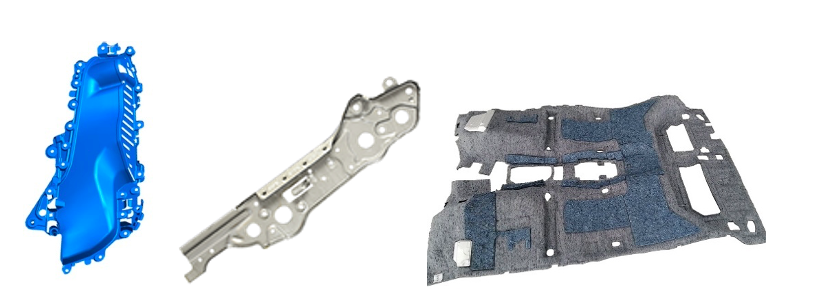

The automotive assemblers in South Africa do not undertake local R&D. They assemble vehicles that have been designed in their R&D headquarters. The same is true for multinational component suppliers. In addition to that, none of the locally owned supplier firms in South Africa conduct their own design or product development. Instead, they produce subcomponents based on design drawings either from the assemblers directly or from subsidiaries of multinational suppliers also operating in South Africa. The most common components that locally owned firms produce are plastic injection mouldings, metal pressings, and trim components. The total lack of local R&D is very concerning, given the historical importance of the development of innovation capabilities in local companies in successful catch-up industrializers. It is not unique to South Africa. As Richard Doner and colleagues show in their recent book on the automotive industry, not even Thailand – which has an auto industry more than three times the size of South Africa – has managed to develop local R&D capabilities.

Locally owned suppliers in South Africa complain about low-profit margins, difficulties to access funding, excessive demands from their buyers regarding certifications, audits, open-book-costing, and production flexibility. They still decide to service the auto industry because it has high and steady demand, as vehicle exports mean production volumes are much higher than they would be if firms were producing only for the domestic market. Domestic demand for vehicles is limited by low incomes and high inequality and has stagnated since 2008.

Looking further upstream, the backward linkages from automotive assembly and component production to the local material industries in South Africa have also been disappointing. South Africa has a local steel mill, two large local polymer producers, and a local aluminium smelter. Nevertheless, by far the majority of the materials for automotive production are imported. It is a consequence of follow sourcing and the fact that material requirements for automotive are incredibly high. BMW does not use the same polymeric material for a car bumper as Mercedes-Benz does. They all have their own standards, formulations, blends, and intellectual property around this. This hyper-diversity of materials reduces the scale of production and thus makes firm-level investments into the local production of materials less attractive.

The scale of production in the South African automotive industry – albeit exporting 70% of final output – is still insufficient to localize more sophisticated components like engines and electronics, materials production, as well as tooling and machinery (almost all tooling is imported; all machinery is fully imported). In contrast to exports of vehicles, exports of components are low (with the exception of catalytic converters based on locally available platinum-group metals). The government tries to tackle this scale problem. The South African Automotive Masterplan aims at upping vehicle production volumes from 600,000 to 1.4 million by 2035. Whether this can be achieved remains to be seen. It is certainly true that if production volumes could be increased, this would help achieve further localization. Some countries with larger production volumes like Thailand have for example managed to localize the production of engines and transmissions (for a comparison of localization achievements of different countries, see here).

The South African picture is not unique. The requirements to get some of the historically important elements of industrialization going, like inter-industry linkages and nurturing innovation capabilities in locally owned firms, have increased substantially compared to the time when South Korea and Taiwan started their automotive industries. The gap between incumbents and followers has widened. Doner and his colleagues show that out of the top 100 global automotive suppliers in 2019, only three came from countries other than from Western Europe, the US, Japan, South Korea and China (Motherson from India, Nemak from Mexico and Iochpe-Maxion from Brazil). Incumbent lead firm power in both assembly and component manufacturing is huge. They undertake most R&D and orchestrate global sourcing of materials and components. Other research demonstrates that the denationalization of automotive industries is commonplace across developing countries, see e.g. here and here.

While it has been emphasized in policy circles that the emergence of GVCs has made it easier for developing countries to enter export markets for manufactured goods and led to increases in local firms’ productivity, the case of the automotive GVC illustrates two major limitations of GVC-based industrialization. The potential for the development of inter-industry linkages and innovation capabilities in developing countries participating in the automotive GVC is undermined by excessive incumbent power, follow design, and follow sourcing.

This blog is based on the PhD research carried out by Tobias Wuttke. The PhD project is on the South African automotive industry, researching the technological capabilities of local component manufacturing firms, linkages from the industry to other domestic economic sectors, and the role of industrial policy. Primary data collected throughout 2021 both online and in South Africa includes semi-structured interviews with vehicle assemblers operating in South Africa, materials producers, multinational automotive component manufacturers, locally owned South African automotive component manufacturers, as well as several interviews with policymakers and industry experts. Some of the research was conducted together with Lorenza Monaco of GERPISA, ENS Paris Saclay.

Tobias Wuttke is a Ph.D. Fellow at Roskilde University, Department of Social Sciences and Business.

Lindsay Whitfield is Professor of Business and Development at the Centre for Business and Development Studies, within the Department of Management, Society and Communication at Copenhagen Business School.