By Lindsay Whitfield and Felix Maile

Earlier last month, Ethiopia was at the center of global attention. The federal Ethiopian government announced a nationwide state of emergency on November 2, as the now one-year-long conflict between the federal government defence forces (and regional militias) and forces led by the Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) threatened to spread from the Tigray region across the country, including the capital city Addis Ababa. The same day, US President Biden suspended Ethiopia’s duty-free access to the US, based on ‘gross violations of human rights by all involved parties in the conflict’. These two developments could mark a turning point for Ethiopia’s emerging apparel export industry, which was labelled the ‘next global sourcing hub’ for the global fashion industry, but also as a potential catalyst for broader industrialization in the country. In the course of the EthApparel research project, we had the chance to speak to some apparel export firms in Ethiopia on what the conflict and the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) suspension means for the future of the industry in Ethiopia.

Ambitious strategy, challenging implementation

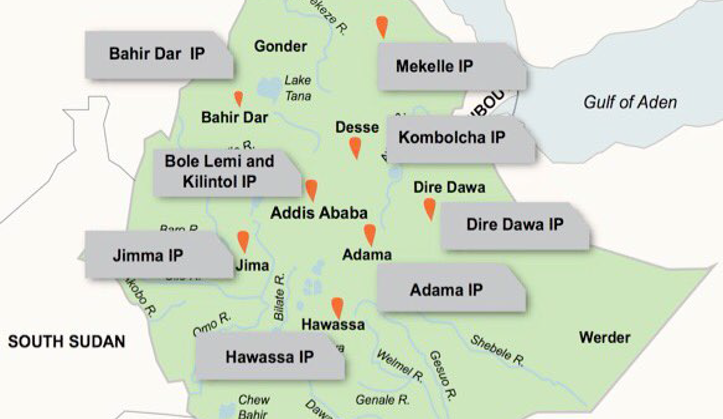

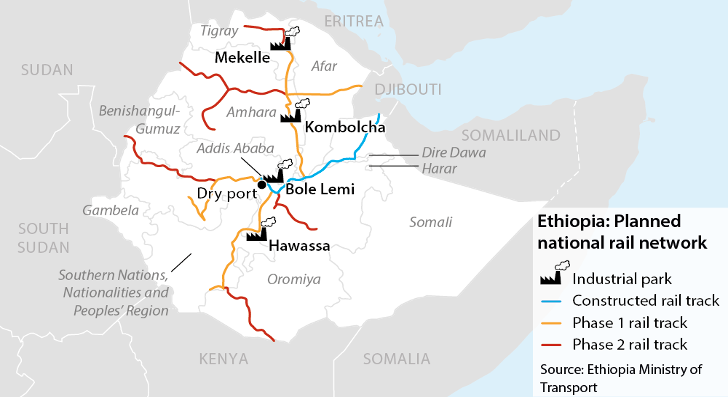

With global fashion brands and retailers aiming to diversify their sourcing base away from China and Bangladesh, Ethiopia seemed to constitute a perfect alternative sourcing location. It offered duty-free access both to the EU and the US market; low production costs related to wage labor, electricity, and water; and the potential to source inputs locally. Additionally, the Ethiopian government provided strategic support to the sector through fiscal and financial incentives as well as the construction of dedicated industrial parks, such as the flagship park in southern Hawassa that opened in 2017. These industrial policies attracted global buyers including PVH Corp., H&M, Calzedonia, and The Children’s Place, which in turn encouraged some of their major suppliers from South Asia and East Asia to take factory sheds in the industrial parks. The Ethiopian government expected apparel exports to generate scarce foreign exchange and significant employment for its growing population, in the second most populous country in Sub-Saharan Africa, as well as constitute an entry point for broader industrialization.

While the initial hype, which was shared by the global buyers, their supplier firms and the Ethiopian government, was substantiated by impressive growth numbers, expectations were not fully met. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, apparel exports grew from $13m in 2010 to $164m in 2019, and employment in the apparel export created jobs for around 72,000 workers by mid-2019. However, these figures are significantly below the targets set by the Ethiopian government within its Growth and Transformation Plan II, which envisioned much higher export revenues ($ 779m) and higher employment numbers of 170,000 for the textile and apparel export sector by 2020.

This lower-than-expected performance can be attributed to different factors. The interest of global buyers stalled after 2017, making it more difficult for the government to fill the sheds in industrial parks that were still being built. The waning interest of buyers occurred as the somewhat naïve narrative of a ‘large, abundant and cheap’ labor force in Ethiopia propagated by the Ethiopian government proved to be more complex. Labor turnover was high and productivity low in existing factories, and new supplier firms found it difficult to source labor: workers were not lining up at their doors, as the government promised. Furthermore, most inputs had to be imported, and transport times were long from land-locked Ethiopia, resulting in long lead times from when buyers placed orders to when they were received. Although more foreign input and textile firms were in the process of being established, locally owned textile, accessory, and packaging firms found it difficult to meet the required quality standards, without direct support.

These shortcomings were acknowledged by the government, which was making efforts to address them, but they were cut short first by the COVID-19 pandemic and then the outbreak of civil war.

Quick COVID-19 recovery, but spreading conflict was the critical turning point

The year 2020 was one of the toughest for apparel global value chains, as store closures in the US and Europe during the COVID-19 pandemic and related order reductions by buyers put massive pressure on governments, firms and workers across apparel supplier countries. This also partly applied to Ethiopia, where exports dropped by around 50% and employment by 10% in mid-2020. However, production in the apparel sector quickly recovered to pre-pandemic levels, as orders picked up again from September 2020 onwards. Furthermore, the outbreak of the conflict in the Tigray region in November 2020 led to an immediate closure of the Mekelle Industrial Park in Tigray, but production continued at the other industrial parks.

Global fashion brands sourcing from Ethiopia did not seem to show much reaction to the conflict and the related reports on human rights violations, and rather remained in a ‘wait and see’ position as long as the conflict remained limited to the Tigray region. Paradoxically, there were even new investments by manufacturers from China, and some suppliers in Bole Lemi industrial park reported to make profit for the first time in 2021 since they started operations in Ethiopia back in 2016.

Notably, then, it was the US announcement of Ethiopia’s suspension from duty-free access to the US market that changed supplier and buyer perceptions of Ethiopia as a sourcing location. Suppliers we spoke with in Bole Lemi industrial park were now questioning whether they would continue their operations in Ethiopia in 2022, despite full order books. This is mainly due to their overwhelming dependence on the US market, which is the destination for around two thirds of Ethiopia’s apparel exports. Some supplier firms even produce entirely for the US market. With the loss of preferential market access under AGOA, these firms will have to pay around 30-35% customs on their respective goods in the US market.

Shifting to the European market — where preferential market access still exists — is a limited option for most firms that we interviewed because they specialize in bulk orders of basic products to US retail chains. Changing their business strategy to one supplying the more fashion-oriented EU market would require time and additional investments. Thus, moving production to other African countries with duty-free access to the US, such as Kenya, is a more feasible option for most firms. The sunk costs in apparel assembly production are not high, especially when factory sheds are rented in government-owned industrial parks and have not been built by the supplier.

The further escalation of the conflict in recent weeks has caused additional fear among these apparel suppliers that the fighting, which is spreading southward, may lead to a cut of the railway connections to the port in Djibouti, from where Ethiopian apparel is shipped to the end destinations, or even reach the industrial park. In mid-November, the anchor tenant of the Hawassa Industrial Park, PVH Corp., announced the closure of its joint venture factory due to the spread of the conflict.

The future is bleak

The Ethiopian government has criticized the US intervention as a biased and ‘misguided’ decision, ‘threatening the livelihood of 200,000 low-income families, mostly women who have got nothing to do with the conflict’. The government also pointed to the fact that previous human rights violations under the TPLF, which governed the country prior to 2018 when political protests led to a shuffle of leadership within the EPRDF coalition government, did not impede Ethiopia’s AGOA eligibility. At the same time, the US government made clear that maintaining Ethiopia’s duty-free access from January 1 onwards would require the allowance of UN agencies to investigate human rights violations, and to end the blockade of humanitarian supply to the Tigray region.

The solution to the spreading conflict, the AGOA controversy, and the survival of Ethiopia’s nascent apparel export industry is a ceasefire between the Ethiopian government and the TPLF-led forces, the resumption of humanitarian aid to the Tigray region, and political negotiations. While there are initial signs that point to a possible diplomatic solution of the conflict under AU mediation, these hopes remain marginal given intensified fights at the frontline. Furthermore, the extent to which ethnic sentiments and propaganda has caused polarization and the spread of hatred in the country is worrying and makes future peace and reconciliation a complex task.

This blog post is part of the research project ‘Decent Work and GVC-based industrialization in Ethiopia’ (EthApparel), funded by the Danida Fellowship Centre. EthApparel asks whether Ethiopia’s integration in the apparel GVC can drive industrialization that is sustainable both from the perspective of supplier firms and workers. The project team brings together researchers from Copenhagen Business School and Roskilde University, Denmark; Open University, UK; University of Vienna, Austria; and Mekelle University, Ethiopia.

Lindsay Whitfield is professor of business and development at the Centre for Business and Development Studies, within the Department of Management, Society and Communication at Copenhagen Business School.

Felix Maile is a PhD student from the Department of Development Studies, University of Vienna. His research focuses on the link between global value chains, financial markets and financialization. In his dissertation, he addresses the question in which way financial markets and investors shape the strategies of transnational fashion corporations, and how this affects the value capture of supplier firms in Ethiopia.

Further Reading

Oya, C., & Schaefer, F. (2021). The politics of labour relations in global production networks: collective action, industrial parks, and local conflict in the Ethiopian apparel sector. World Development, 146, 105564.

Whitfield, L., Staritz, C., & Morris, M. (2020). Global Value Chains, Industrial Policy and Economic Upgrading in Ethiopia’s Apparel Sector. Development and Change, 51(4), 1018-1043.

Whitfield, L. and Staritz, C. (2021). The Learning Trap in Late Industrialization: Local Firms and Capability Building in Ethiopia’s Apparel Export Industry’. Journal of Development Studies 57(6): 980-1000.