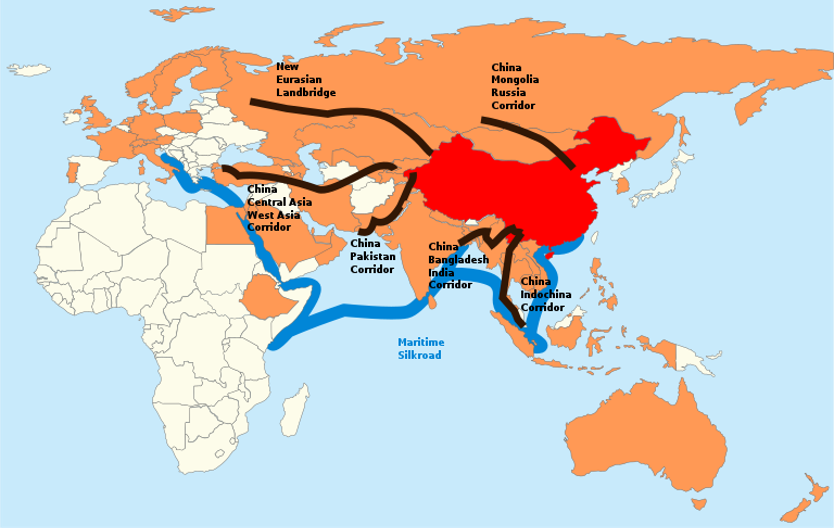

This year marks the tenth-year anniversary of Xi Jinping’s proposal for an “economic belt along the silk road” while on a diplomatic mission to Kazakhstan, what would later become the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) or One Belt One Road (OBOR) in Chinese (一带一路). Chinese state-owned firms, under the umbrella of the Belt and Road Initiative, have built pipelines, railroads, roads, ports, and other infrastructures, especially in regions that private investors deem too risky to invest. The Chinese government estimates that it has spent 1 trillion USD for the development of transportation and energy infrastructure and other infrastructure projects in over 3000 projects globally. This spree of infrastructure building has captivated policymakers focused on the rise of Chinese economic and political international influence. The BRI has also led to contentious global politics around investments and has intensified geopolitical competition between China and the US. This post discusses the last ten years of the BRI and the ways in which it is evolving.

Belt and Road Initiative as the cornerstone of Xi Jinping’s foreign policy

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) pledged massive infrastructural investment to enhance the connectivity of China with the rest of Asia, Africa, and globally. It also became discursively entrenched with the foreign policy strategy of Xi Jinping. Although other Chinese policymakers had already promoted the idea of outward Chinese investments, such as the ‘go out policy’ initiated by Jiang Zemin in 2000, the BRI was the first time that a Chinese outward investment strategy had been articulated directly as foreign policy (as stated in state council guidelines in 2015). The BRI was then imprinted into the Chinese communist party constitution in 2017 as a central element of foreign policy. In so doing, all layers of the Chinese government apparatus, and its economic arms: banks, and state-owned firms became involved in the development of infrastructure investments abroad.

Source: https://denstoredanske.lex.dk/%22Belt_and_Road%22-initiativet;

license: CC BY SA 4.0.

Empty ports? Successes and failures of the BRI in its first ten years

Although much attention has been placed on massive ‘white elephant’ projects such as the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor and all its subprojects, the reality is that the projects included within the BRI framework vary dramatically in size and scope. At the same time, the success or failure of projects has been hard to determine.

Apart from promised projects that have not yet materialized, as it is the case for example of Bagamoyo port, cancelled by Tanzanian authorities after a change in government (and now perhaps getting restarted after a new change of government in Tanzania), projects that have been constructed have had less than advertised results. For example, the much-discussed Gwadar port in Pakistan is one of the most used examples of infrastructure developments under the BRI not delivering expected economic results. Gwadar port not only has underperformed economically, as it has not provided a suitable alternative to the congested Karachi port, but it has also exacerbated the difficult political situation in the Balochistan region of Pakistan. The port is the center of many protests and is used as an image of the weakness of the Pakistani government and its subdued relationship with China. At the same time, many China-Pakistan Economic Corridor projects in the region surrounding the port continue to materialize, such as industrial parks and special economic zones, a highway linking Gwadar all the way to the Chinese border with Pakistan. As these other projects continue in the region, they could change the commercial landscape for the port.

Finally, as many other scholars have discussed in relation to Chinese investments abroad, local agency is important. Not only had Gwadar port been on the planning table of Pakistani authorities for over 20 years, but the Pakistani government insisted on its inclusion as part of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor even as Chinese commercial actors showed no interest in the project. This showcases both the way in which local authorities and local politics shape projects but also the way in which different Chinese firms and authorities have maneuvering room to decide which projects to be a part of within the fragmented Chinese institutional politics.

The next ten years – new directions for the BRI

The 3rd Belt and Road Forum celebrated this October 17th and 18th in Beijing, marks the official celebration of the tenth anniversary. It did so by pledging 100 billion USD in new investments and by highlighting a shift in focus for the BRI. From pure infrastructure development to a focus on digital services, green development, and renewable energy projects as well as more ‘soft’ collaborations. For instance, one of the twenty new collaborations signed between China and Pakistan included a one-year agreement for knowledge transfer port development and management for the Gwadar port, indicating perhaps the focus of the BRI moving away from pure infrastructure building and into making existing investments commercially viable.

Nonetheless, one key outcome of the 3rd Belt and Road Forum has been to highlight its continued relevance, particularly for the global south, with many heads of state present and making new investment deals with China. Even in the times of continued and growing geopolitical contestation between East and West and continued calls for decoupling or de-risking from China. The BRI forum reminds us to not underestimate the relevance of China for the global economy and global trade.

Listen to the Business in Development Podcast and find out more!

The Belt and Road Initiative at ten, geopolitics and China’s role in global development

Professor Lindsay Whitfield from CBDS discusses the tenth anniversary of the Belt and Road Initiative, the contentious politics it engenders, and the role of massive Chinese infrastructural investments globally with Dr. Federico Jensen, external lecturer at Copenhagen Business School. In the episode, they discuss the origins of the Belt and Road Initiative, it’s economic and political successes and failures, and the role of local governments in investment receiving countries.

Listen in your favourite podcast app

Further reading:

Jones, L, & Hameiri, S. (2021) Fractured China, How State Transformation is Shaping China’s Rise. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge

Lee, C. K. (2017). The Specter of Global China: Politics, Labor, and Foreign Investment in Africa. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

Ye, M. (2020). The belt road and beyond: State-mobilized globalization in China: 1998–2018. Cambridge University Press. NY, USA

Federico Jensen has recently finished his PhD at Copenhagen Business School. His academic work centers around the international political economy of maritime shipping and offshore industries.