By Christina Plesner Volkdal

Amid escalating humanitarian crises, protracted conflicts, and overlapping global disruptions, multilateral institutions are under renewed scrutiny. The demand for more coherent, inclusive, and sustainable responses has propelled the rise of the “Triple Nexus” framework – an integrated approach that seeks to align humanitarian aid, development strategies, and peacebuilding efforts. Yet, translating this framework into institutional reality remains a challenge. A recent series of CBDS policy papers interrogates this challenge through comparative analyses of the United Nations (UN) system and the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC), revealing structural gaps and offering strategic pathways for reform.

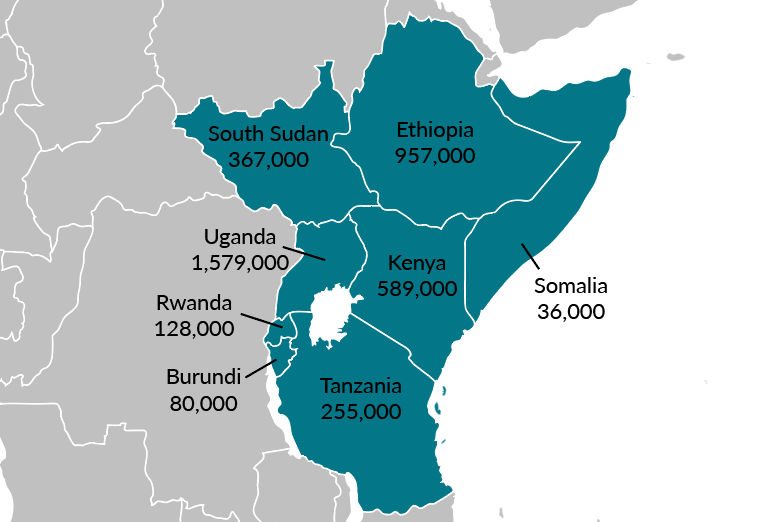

The first policy paper examines how six key UN agencies – United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), World Health Organization (WHO), World Food Programme (WFP), Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), and International Labour Organization (ILO) – engage with the Triple Nexus framework. While rhetorical alignment exists across the system, implementation remains fragmented. The analysis uncovers significant divergence in governance models, integration capacities, and financing mechanisms. Agencies such as WHO and ILO demonstrate stronger governance coherence, yet still encounter operational bottlenecks. Others, including FAO and WFP, struggle to institutionalize peacebuilding within their sector-specific mandates. The paper argues that political economy constraints – ranging from donor-driven priorities to rigid bureaucratic procedures – undermine Nexus implementation. It recommends a shift toward integrated governance structures, pooled and flexible funding, and localization strategies that prioritize adaptive, context-sensitive programming.

The second paper turns to the OIC, whose humanitarian operations are hampered by fragmented coordination and limited institutional capacity. Despite its reach across 57 member states, the OIC lacks a centralized humanitarian architecture capable of delivering timely, resilient responses. This paper calls for the establishment of an OIC Humanitarian Operations Centre and a regional Disaster Risk Reduction framework. It further proposes the integration of the Triple Nexus as a guiding principle – connecting emergency relief with development financing and peacebuilding mandates. Drawing lessons from the Association of Southeast Asia Nations (ASEAN) and the African Union (AU), the paper emphasizes localized preparedness, digital innovation, and multi-year investment strategies to enhance institutional resilience and programmatic coherence.

The third policy paper critically assesses the OIC’s role in peace and security. Unlike the UN, AU, and the European Union (EU), the OIC lacks a dedicated peace and security infrastructure, relying instead on ad hoc diplomacy and non-binding resolutions. The paper proposes the creation of an OIC Peace and Security Council, a Mediation and Crisis Response Unit, and a Standby Force capable of rapid deployment. It also recommends the establishment of a Peace and Security Fund grounded in Islamic financial instruments such as zakat and sukuk. These institutional reforms, the paper argues, are essential for transforming the OIC from a rhetorical actor into an effective agent of conflict resolution and peacebuilding.

Together, the three policy papers underscore the urgent need for institutional innovation within multilateral systems. Whether at the global level within the UN or the regional level within the OIC, the operationalization of the Triple Nexus remains hindered by structural fragmentation, financing gaps, and insufficient coordination. Addressing these challenges requires more than technocratic adjustment – it demands a political and institutional reimagining of how global governance engages with complexity, crisis, and change.

Christina Plesner Volkdal is a PhD Fellow at Copenhagen Business School, affiliated with the Department of Management, Society, and Communication. With a background in the UN, particularly in humanitarian coordination, and an approach as a participant observer, she leverages first-hand experiences to offer profound insights, enriching her contributions to the field.