By Ruth Wairimu John as part of the NEPSUS Series

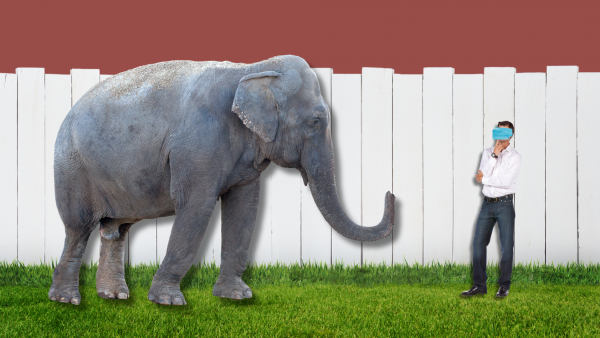

When I joined the NEPSUS team in 2016 as a PhD candidate, I didn’t expect to come across wild animals in the villages. On the day of my arrival to Mloka village in March 2017, I immediately bumped into elephants at Selous Kinga Lodge. Mloka is one of the villages bordering the Selous Game Reserve, the largest and oldest game reserve in Africa. I was shocked by the appearance of elephants so close to the lodge’s bar and wondered if it is common to see elephants in the village, perhaps even approaching the villagers’ private houses. At midnight, I suddenly woke up when I heard noises of people shouting. I looked through the window and recognized a crowd of people passing by, yelling and trying to chase away an elephant that was eating fruits at the local market.

The next morning, I wanted to find out what exactly had happened during the night. The villagers showed me the leftovers of the fruits at the local market, where the elephant had eaten during the night. From that day on, I perceived it as normal to come across elephants in the village, though encountering wildlife can be dangerous. I was very cautious when walking through the village, especially when I was heading to a key informant interview at one of the houses located outside of the center and closer to the reserve.

The lion that killed 40 people

Among the memorable stories of wild animals in Rufiji district is that of a lion which killed about 40 people and injured more than 20 people in 2004/2005. The male lion lingered around the villages for more than six months, attacking people in their upstairs houses, called “Vidungu” in Swahili, killing and eating them. These upstairs houses are used during day and night to protect crops on the farmland from being destroyed by wild animals. When the lion came to understand that villagers were sleeping in the “Vidungu”, it started to attack them during the night. The rangers, in collaboration with the District Game Office, needed over six months to find and finally kill the lion. The villagers at Ngorongo village told me that many people attended the lion’s funeral and that they had put up a sign where the lion was buried.

Close encounters

During my fieldwork, I encountered a lot of wildlife. One day, I was interviewing an old woman about the history of Mloka village. She suddenly went quiet and told me to look at my right side. I recognized big elephant standing a few meters away from us in the backyard. I asked the old woman what we should do and she told me to be silent, as the elephant would just pass and go up to the village, where it had eaten the fruits at the local market before.

Protecting wildlife, threatening livelihoods

After a few weeks I travelled to Ngorongo village, where I shared my elephant story with some elders from the village. They responded that they did not perceive it as a shocking story, since they live and co-exist with these animals and still feel safe in the village. They considered it tolerable that wild animals eat and destroy crops on the farms, since they have already coped well with these challenges for many years. This view persists, though the government has not yet introduced a sufficient compensation scheme which could help the villagers to limit the damage caused to their livelihoods. The consolation scheme provided by the government is not adequate; the process of soliciting compensation is very time-consuming and can take years to be resolved. Moreover, the local institutions lack capacity for dealing with wild animals that cross the borders and enter the villages. Sometimes, even when game rangers chase elephants back to the game reserve, they come back just after a few hours.

Villagers perceive that elephants are more protected than human beings. When elephants destroy or eat crops from the local fields, the only action taken by the government is to chase them away, using light bullets that cannot kill them. After a few days, the elephants come back. During harvest time, the villagers have no other option than taking from the field what the elephants have left. From the day of planting the seeds to the last day of harvest, the villagers have to stay close to their fields, chasing elephants away as they raid crops, damage assets and sometimes even kill people.

Conservation efforts by the government have also led to a ban on resident hunting in villages adjacent to the game reserve. Therefore, since 2016, local villagers have lost legal access to wild meat, a main protein source that is vital to their nutrition. Lack of alternatives often leads to illegal crossings, hunting and fishing in the game reserve. This is problematic as illegal hunting and fishing puts lives at risk, especially among young members of the rural community. It also worsens the relationship between game rangers and local villagers and undermines conservation goals.

The controversial role of wildlife tourism

Despite the difficulties that wild animals cause for the local population, they also represent a potential source of income. As the villagers in Mloka said, it is possible to feel safe in the presence of wildlife. Not all wild animals represent a threat and are likely to attack. With some animals, a peaceful cohabitation is possible. This can be very beneficial for the local population, as more wildlife makes a location attractive for tourism. However, in order to get profit, villages have to be able to capture revenues from wildlife tourism.

In reality, this often proves difficult as the business of wildlife tourism takes place beyond their control. In order to capture revenues, the local population has to enter into a partnership with well-connected and financially strong individuals and companies. The presence of dangerous animals increases the village’s value for business. Mloka village, where I stayed most of the time during my fieldwork, is an entry point to the Mtemere gate of Selous Game Reserve (SGR). The villages in this region have attracted over 30 private investments for tourism.

Our research project (NEPSUS) seeks to examine how these partnerships have operated and simultaneously changed the way people see and experience wildlife in their backyards. To non-locals, a village where wild animals are regularly present is obviously considered good because it could attract wildlife tourism.

The manager of one of the camps told me that he was very happy because they were blessed to observe a leopard moving around the lodge during the night. Instead of being afraid of the leopard, the manager was content because his customers enjoyed watching it. So is everyone happy? Certainly not. Wildlife is perceived differently by local residents and by business people.

The relationship between villagers and their business partners can be conflictual. When applying for a permit to conduct business in the villages, investors have to assure in writing that they will help improve social services and employ a majority of local residents. But some of the companies do not stick to their commitment. The number of employees coming from outside the villages very often outnumbers local employees. At the same time, villagers suffer from attacks by wild animals while business benefits.

Love them, hate them

The local population has no other option than to learn how to live with the presence of wild animals, in particular with elephants. Although they are the most powerful animals in the wild, sometimes villagers even have to save them. A previous blog post described the story of a baby elephant that got stuck in a well and had to be rescued. The daily human-wildlife interaction becomes evident as villagers even named some resident elephants after local people. They are able to identify the type of wild animal by observing the foot prints.

The villagers said that buffaloes, unlike elephants and other animals often stay at the village without being seen, eating maize from the farmlands during the night. Hippos also move around the village land at night time. The Village Game Scout (VGS) and villagers showed me footprints of wild animals in the village as shown in the photos below:

For local people, however, wildlife is not as interesting as it is for tourists. It is a daily reality they have to put up with. Our fieldwork showed that living next to Selous Game Reserve poses serious challenges to rural communities in the name of conservation. The conservation of wildlife creates benefits for business operators and threats to local livelihoods. Ensuring that villages benefit from tourism, securing rural livelihoods and successfully overcoming human-wildlife conflicts are the main challenges on the way to sustainable conservation.