By Felix Maile and Lindsay Whitfield

As part of our ‘Creating and Capturing Value’ project, we seek to investigate the drivers for (uneven) value distribution between fashion brands, supplier firms and workers in the global apparel industry. As we learned during our recent three weeks of fieldwork in South Korea and Hong Kong, understanding value capture outcomes in globalized industries requires moving away from a single country case study focus, and instead consider the global portfolio of transnational suppliers that connect global buyers with a range of producing countries.

In the past two decades, we have seen the rise of strategic ‘mega suppliers’. These transnational apparel suppliers operate manufacturing facilities across different continents, and perform logistics, design and input sourcing functions for global fashion brands and retailers. Some scholars have argued that this novel type of supplier firm shifts the power balance towards a ‘bi-polar’ configuration of the apparel GVC, in which strategic transnational suppliers are able to capture significantly more value than smaller local supplier firms. But measuring and explaining whether these functions, combined with a transnational production portfolio, ultimately change the power dynamics in GVCs is not an easy undertaking.

The most commonly used approach of GVC researchers to investigate buyer-supplier relations and value capture outcomes is centered on semi-structured interviews in a specific case study country. This method is indeed useful to obtain the perspectives of a number of key informants in a particular country, including local supplier firms, government representatives, buyer sourcing offices, or trade unions. But as we experienced during fieldwork in Ethiopia and Kenya in 2022 and 2023, the country case study approach faces substantial limitations in understanding the overall business strategy of transnational mega suppliers and its implications for value capture outcomes.

We thus shifted the focus in our research to a firm centered case study approach, selecting a sub-set of the largest transnational suppliers from Asia. We decided to focus on 8 transnational supplier firms from South Korea (4) and Hong Kong (4), as these firms were vital in the expansion of the global apparel industry, given that they operate giant facilities in major sourcing hubs like Bangladesh, Vietnam or Cambodia and supply the largest global fashion brands and retailers. Some of them also have subsidiary factories in Ethiopia and Kenya. We also benchmarked these 8 firms to the two of the largest apparel suppliers in terms of gross profit volume and margin: Shenzhou (mainland China) and Eclat (Taiwan).

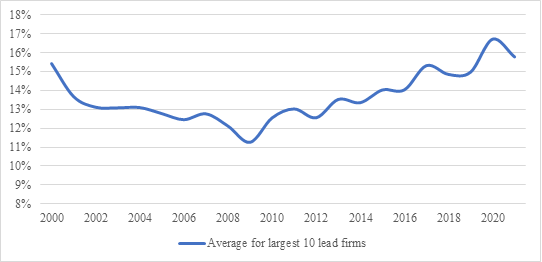

As a first step, we conducted research on each firm based on available information on the web and publicly available profit and revenue data to create an overview of each firm’s history, the development of its transnational production locations and capabilities, its buyer relationships, and its value capture trajectories. As Figure 1 shows, there are significant differences in value capture among the largest transnational apparel suppliers, as some firms capture more than 25% gross profit margin while others fall below 20%.

Figure 1: Annual gross margins (%) of top apparel FTS from Hong Kong, Korea, China and Taiwan

Note: Two of the Hong Kong firms are not in Figure 1 because they are not publicly listed companies and thus their financial data is not publicly available, and the two firms were not willing to share their financial data.

As a second step, we sought to explain variation in the value capture outcomes of the 8 transnational apparel suppliers based on interviews with senior managers at their headquarters in Hong Kong and South Korea, which we conducted during August and September 2024. These interviews provided the unique opportunity to understand the overall supplier firm strategy, the rationale to invest in certain countries and functions, and the inherently contradictory relationship with global fashion brands and retailers. The buyer-supplier relationship, even at this level of transnational supplier firms, is characterized by both strategic collaboration on product innovation and market growth, but also fierce struggle over margins.

Visit at headquarter of Hansae in Seoul, Korea, September 2024

Note: Hansae is one of the largest transnational apparel suppliers and operates factories across Southeast Asia, South Asia and Central America.

Our interviews suggest that neither establishing a transnational production portfolio nor performing additional tasks are sufficient factors to alter the bargaining power of suppliers vis-à-vis global apparel brands and retailers. Rather, what is required to capture more value are unique and complementary capabilities that make that specific transnational apparel supplier indispensable to the business strategy of the apparel brand/retailer (at least for a time period) and allow it to create barriers to entry that keep other transnational supplier firms from emulating those capabilities (at least for a time period).

We discuss these findings in a forthcoming paper: ‘Capturing value in a buyers’ market: Supplier value capture trajectories in apparel global supply chains’. So stay tuned. This blog post was first published on the Creating and Capturing Value in the Global Apparel Industry website: https://www.creatingcapturingvalue.org/post/conducting-multi-sited-fieldwork-to-investigate-transnational-capital-in-gvcs

Felix Maile is a doctoral researcher in development economics at the University of Vienna.

Lindsay Whitfield is a professor of business and development at Copenhagen Business School.