By Felix Maile and Cornelia Staritz

Who captures most of the profits created in the global apparel industry? When discussing distributive issues in apparel global value chains, scholars, policy makers and activists tend to focus on distributive struggles between five groups of actors: Consumers, fashion brands and retailers, manufacturers, workers, and states. Much of the analysis concludes that the rise of global value chains since the 1990s has enabled fashion brands and retailers (also known as ‘lead firms’) to capture juicy profits, and consumers to benefit from low-cost yet fashionable apparel products. By comparison, manufactures operate with razor thin margins and workers are exposed to harsh working conditions and low wages. States in turn earn limited taxes, given the investment and sourcing attraction policies that are common in special economic zones through which many supplier countries are integrated in the apparel industry. Yet, this analysis factors out one group of actors that is central in distributive matters: The shareholders that own the fashion brands and retailers and that have the claim on the profits that these lead firms generate. In this blog, we question the dominant perception of stock markets serving as the major ‘source of finance’ for apparel corporations to run their operations. Analyzing patterns of value creation and capture as well as corporate financing in the past 30 years, we come to a different conclusion: Stock markets barely contribute to apparel lead firms’ financing. Instead, apparel lead firms have funded stock markets, based on the profits that they generated vis-à-vis manufacturers and workers in their value chains.

In order to understand the distribution between shareholders and actors in global value chains, we draw on the conceptual and methodological toolbox of the corporate financialization literature. This strand of work emerged in the early 2000s, seeking to make sense of a shift in corporate strategy and management practice towards ‘shareholder value’ that had been underway since the 1980s: Financialization scholars have analyzed the balance sheets and income statements of major corporations in order to trace their sources of funding and understand how profits are created and allocated.

The seminal financialization literature of the early 2000s concluded that large firms had shifted their strategy from ‘retain and invest’ to ‘downsize and distribute’. What they meant was that formerly vertically-integrated firms shifted away from reinvesting profits in ‘productive’ means such as machinery, their workforce, or research and development. Instead, they outsourced less profitable parts of the value chain, often to firms based in lower-cost countries, and disbursed their profits to shareholders, either via dividend packages or so called ‘share buybacks’, in which companies repurchase their shares to boost their stock price. Financialization and globalization are therefore closely interrelated and reinforcing processes in the global economy.

More recent contributions challenged this seminal literature by highlighting the dramatic acceleration of corporate financialization since the turn of the millennium, which changed its characteristics. Central to this were two processes: Globalization expanded on a different scale, with China’s WTO entry in 2001 providing low-cost global value chains centered around China as a backbone of accelerated outsourcing and offshoring, and shifts in financial markets created a low-interest rate environment. This changed the profit capacity of transnational corporations: Rather than ‘downsizing’, transnational corporations have merged, and monopolized global consumer markets both in high income and in emerging economies. Because their dominant position required fewer investments, and low interest rates during this period reduced financing costs, transnational corporations loaded incurring super profits on their shareholders.

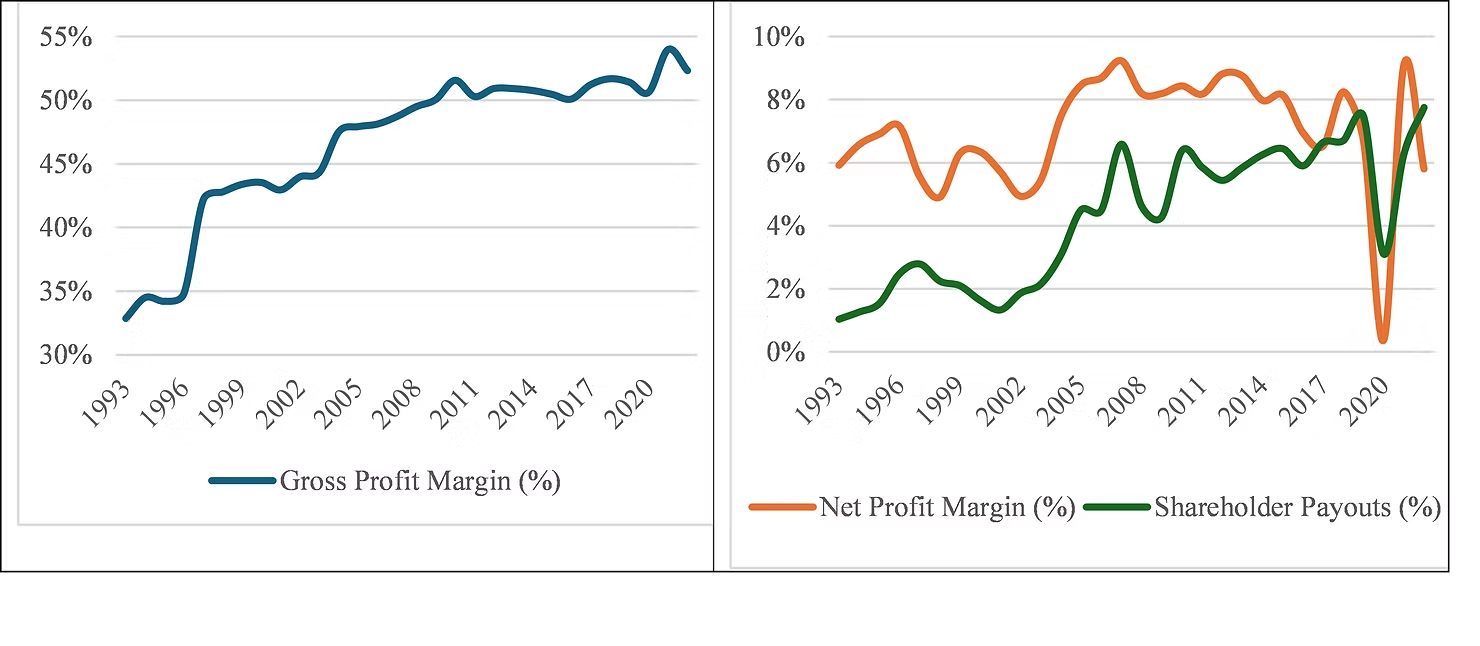

This is precisely what happened in the global apparel industry: Since the early 2000s, the ten largest apparel lead firms by annual turnover have quadrupled their revenues, by expanding in established end markets such as the US, Europe, and Japan, but especially in China. The liberalization of apparel trade as well as China’s entry into the WTO in 2001, which soon thereafter accounted for 40% of global apparel exports, put apparel lead firms in a structurally advantageous bargaining position vis-à-vis manufacturers, workers, and supplier countries. As Figure 1 (blue line) depicts, the hyper-competition in the supply base allowed these ten firms to boost profits realized on goods sourced (‘gross margin’) dramatically, from 33% in the mid-1990s to more than 50% by 2010. At the same time, net profits during the same period (orange line) barely exceeded 8%, because apparel lead firms made hefty expenses on their distribution network as well as in brand building and marketing, which is the essential competitive advantage for apparel corporations. However, an ever-larger chunk of these net profits was disbursed to shareholders: Expenses for dividends and share buybacks (‘shareholder payouts’, green line) rose dramatically, from 1,6 % of annual revenue in 2000 to 7,8% in 2022.

Note: The top ten apparel lead firms were selected based on their 2022 revenue. These firms include Nike, Inditex, Adidas, H&M, Fast Retailing, Gap, PVH, VF, Ralph Lauren, Levi’s. To control for global value chains dominated by apparel firms, we excluded high revenue brands that are part of multi-segment luxury conglomerates (LVMH, Kering) and wholesale retailers (Walmart, Target)

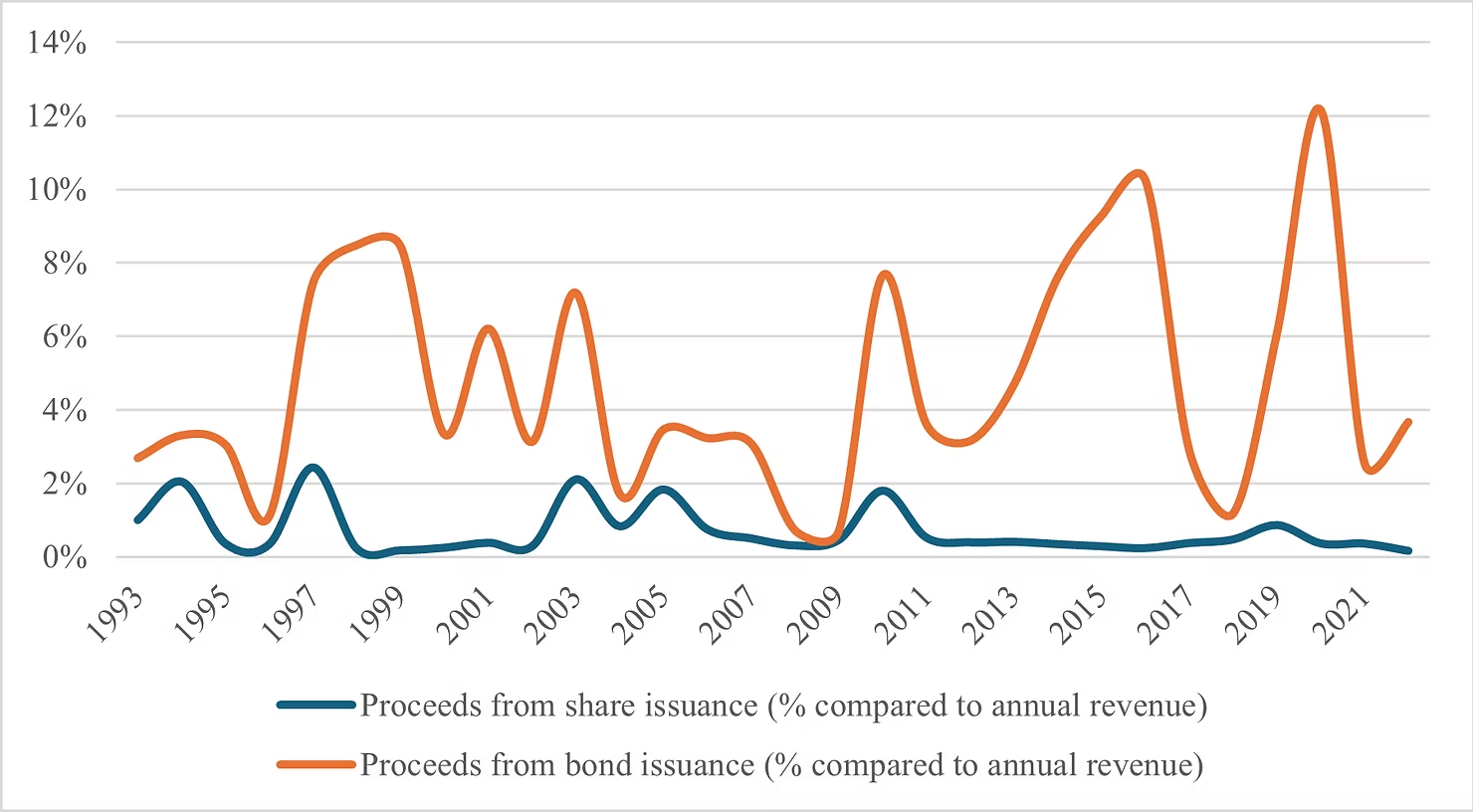

While apparel lead firms have distributed the bulk of their profits to shareholders, it is striking that they have barely used stock markets as a source of funding. Figure 2 shows that the annual proceeds lead firms generated from stock issuance since the early 1990s have been fairly meager (blue line), accounting for 0,7% when compared to annual revenues. Most apparel corporations had their public offering on stock markets during the 1970s to 1990s, through which they raised a few hundred million US dollars at the time. Afterwards, new share issuance was rather the exception than the norm. Once these firms turned global, the payouts to shareholders began to amount to several billion US dollars per year. By comparison, the central source of finance for apparel lead firms in the past 30 years have been bonds markets. Proceeds from corporate bonds accounted for 4,7% of revenue on average during that period (orange line), thus exceeding the funds secured from stock issuance by 7 times.

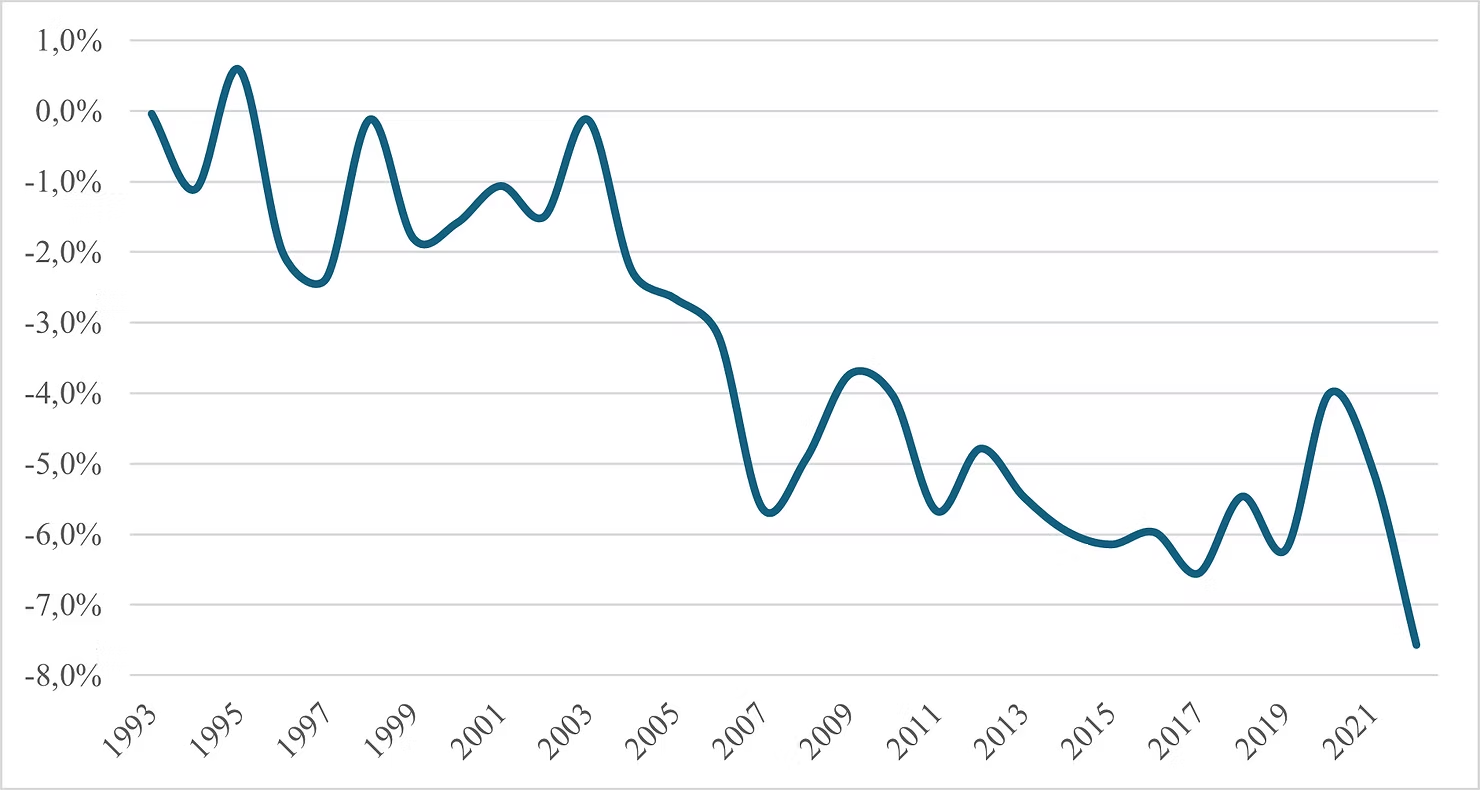

The distributive relationship between apparel lead firms and their shareholders thus turned into a one-way street. Since the mid-1990s, net financial flows from lead firms to stock markets have been negative for all financial years. By 2022, this net negative finance flow accounted for on average 7,8%, when measured against lead firms’ annual revenues.

Note: Net financial flows are calculated by comparing annual stock issuance with annual shareholder payouts, benchmarked against firms’ revenues.

These results raise broader questions about the role of stock markets in global capitalism. Stock markets perform an array of functions: They are an institution of corporate control. Corporations also make use of their own shares as a currency to pay for acquisitions of other firms, and to remunerate their top executives. Stock markets further serve as an institution for ‘firm creation’, because the outlook for an initial public offering acts as a magnet of funding for early stage firms. Finally, as the market turmoil in recent weeks has shown, stock markets have become the central global institution of wealth management, on which institutional investors such as insurances, pension, sovereign wealth funds, hedge funds, but also wealthy individuals and retail investors seek to optimize their investment portfolios. But counterintuitively, stock markets do not function as a significant source of finance for firms. Instead, major transnational corporations, with fashion brands and retailers as a prime example, channel the profits created in global value chains to their shareholders.

Understanding global distributional inequality thus requires linking value creation in globalized production with value capture in global financial markets. The starting point for this is to acknowledge and understand the role of financial markets and actors as one of the main beneficiaries of globalized production, how they impact the business and sourcing strategies of (lead) firms, and ultimately shape the value capture of governments, manufacturers and workers integrated into apparel global value chains.

Felix Maile is a doctoral researcher in development economics at the University of Vienna.

Cornelia Staritz is Associate Professor in Development Economics at the Department of Development Studies at the University of Vienna.

This blog post has first been published here.