By Florian Schaefer

We have been collecting data on firms and workers in the apparel export sectors on Kenya and Ethiopia to help us better understand the opportunities and challenges that apparel production can bring. The Creating and Capturing Value in the Global Apparel Industry project aims to explain what determines the wages and working condition in supplier firms, and how these can be sustainably improved. This blog post draws on some of the initial results from surveys administered to apparel factory workers in Kenya and Ethiopia to explore the factors that both drive wages and limit wage growth.

Apparel export production in Kenya and Ethiopia

The apparel export industries in Kenya and Ethiopia are relatively small, compared to Asian countries, and mostly include simple apparel assembly. Growth over the last decade was driven by a combination of rising wages in Asia, buyer preferences for diversification into new locations, and tariff-free access to the US market through the African Growth and Opportunity Act, although Ethiopia lost this tariff preference in 2022. Most apparel exporting firms in Ethiopia and Kenya are large supplier firms with production bases in Asia who move or expand small shares of their production, but there are important differences between the two countries. The Ethiopian industry is very recent in origin and exporting firms are largely concentrated in a series of new industrial parks, which were supposed to provide access to cheap electricity and low wages. Most firms that export apparel from Ethiopia are large transnational first tier suppliers. By contrast, the sector in Kenya is much older, with higher wages and more productive workers. Exporters are either large transnational producers or smaller single-factory operations, some of whom act as subcontractors for larger exporters.

Wages depend on decision made across multiple sites and scales

To understand wages paid to production workers in apparel supplier factories in East Africa, or any other production location, we need to trace the pressure for lower wages through the supply chains that define the global apparel industry. As we have documented in previous posts, the global apparel sector is dominated by large buyers, generally multinational enterprises that are able to manage access to lucrative consumer markets through their control of dominant brands or retail operations. Such apparel buyers have been able to build up high levels of bargaining power vis-à-vis their suppliers.

Apparel supplier firms are forced to produce clothes at or below a global ceiling price. Buyers will determine a maximum price they are willing to pay for a particular product and supplier firms that cannot meet that price will no longer receive orders. This trend has been especially apparent in apparel assembly. In short, global buyers want to optimise financial results. They pass this pressure on to supplier firms, who then must seek to become – or remain – profitable within the global ceiling price set by buyers. To survive supplier firms must try to achieve a combination low wages and high productivity, which often means strict factory discipline.

Given that apparel buyers determine an effective global ceiling price that binds all supplier firms engaged in apparel assembly, we hypothesize that the wages paid to workers in supplier firms in Kenya and Ethiopia should not differ significantly across firms in the same production location. Rather, wages will vary across production locations due to differences in local labour markets (including institutions and labour laws) and the extent to which workers are able to effectively mobilise for higher wages and better conditions.

How we find out: matched employer-employee surveys

To help us understand wages differences, we built a unique dataset of matched employer-employee data of firms and workers in the apparel sectors of Ethiopia and Kenya. Our wage data comes from direct interviews with production workers in both countries. Our quantitative dataset comprises two sources. In Kenya, we conducted our own worker and firm survey as part of the Creating & Capturing Value Project (N~400), while in Ethiopia we used a worker and firm survey conducted for the ILO Siraye programme in Ethiopia (N~1,000). In addition, to help us contextualise and interpret our findings, we conducted a large number of qualitative interviews in both countries. What did we find?

Wages are not systematically higher in larger firms

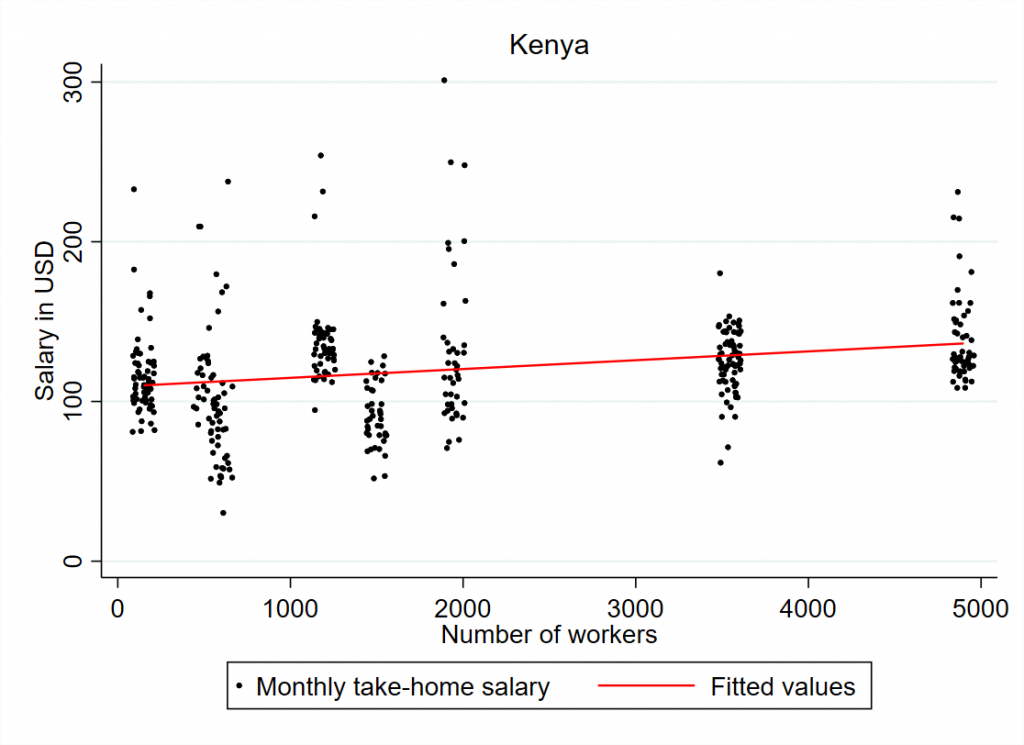

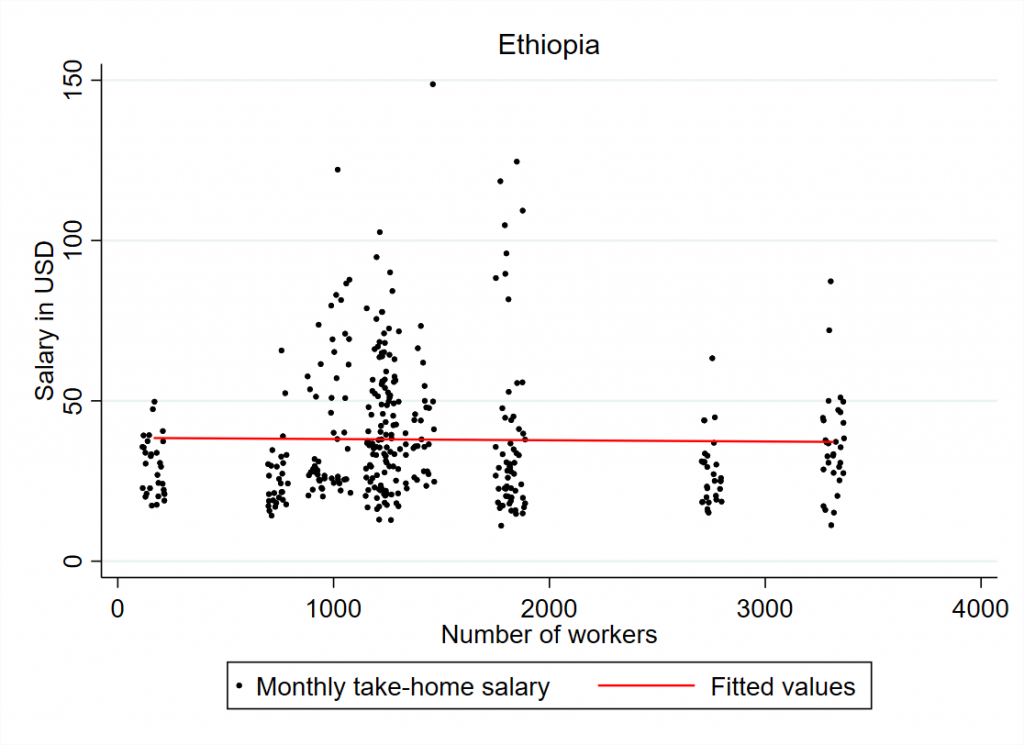

We first explored the relationship between salaries and firm size, using firm size as a proxy for the sophistication of the company given that the larger firms in the industry tend to be transnational first tier suppliers. Figure 1 shows the results for both Ethiopia and Kenya. In Ethiopia, there is no relationship between the wages paid to production workers and the size of the supplier firm. In Kenya, there is a positive relationship, meaning that larger firms do pay slightly higher wages, though the relationship is quite weak. In both countries, firm size is not a convincing predictor of wages paid to production workers. We can also see how much higher workers’ wages are in Kenya compared to Ethiopia. Using market exchange rates at the time of each survey to convert to USD, i.e. not correcting for differences in purchasing power, we find that the mean salary in Ethiopia was just $38 compared to $120 in Kenya.

Figure 1. Salaries and firm size in Ethiopia and Kenya

Wages differ across production locations in the same country

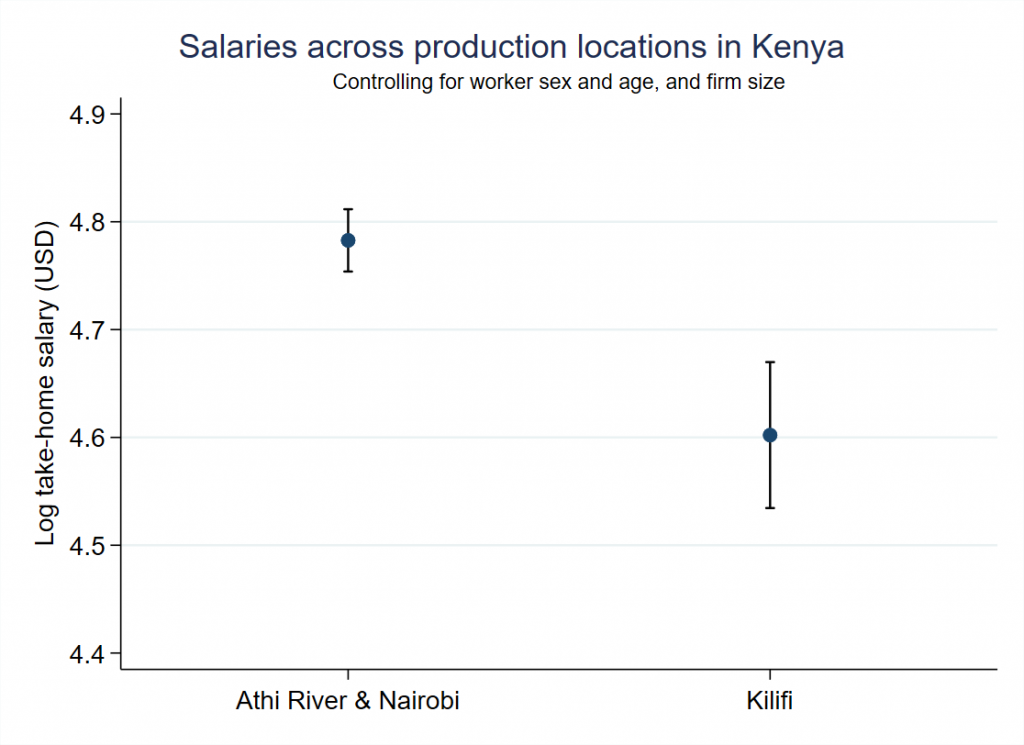

Next, we examine differences in wages across production locations. We do this separately for Kenya and Ethiopia, due to the large institutional differences between these countries. To make sure that any differences we find are meaningful, our analysis controls for basic worker characteristics such as age and sex, and firm characteristics such as size and level of worker unionisation. In Kenya, there are very clear differences between the two major production locations, Athi River and the Kilifi area near Mombasa. Athi River is effectively a suburb of Nairobi, while the firms we sampled in the Mombasa area were all outside of the city itself. Workers in Athi River had much higher wages.

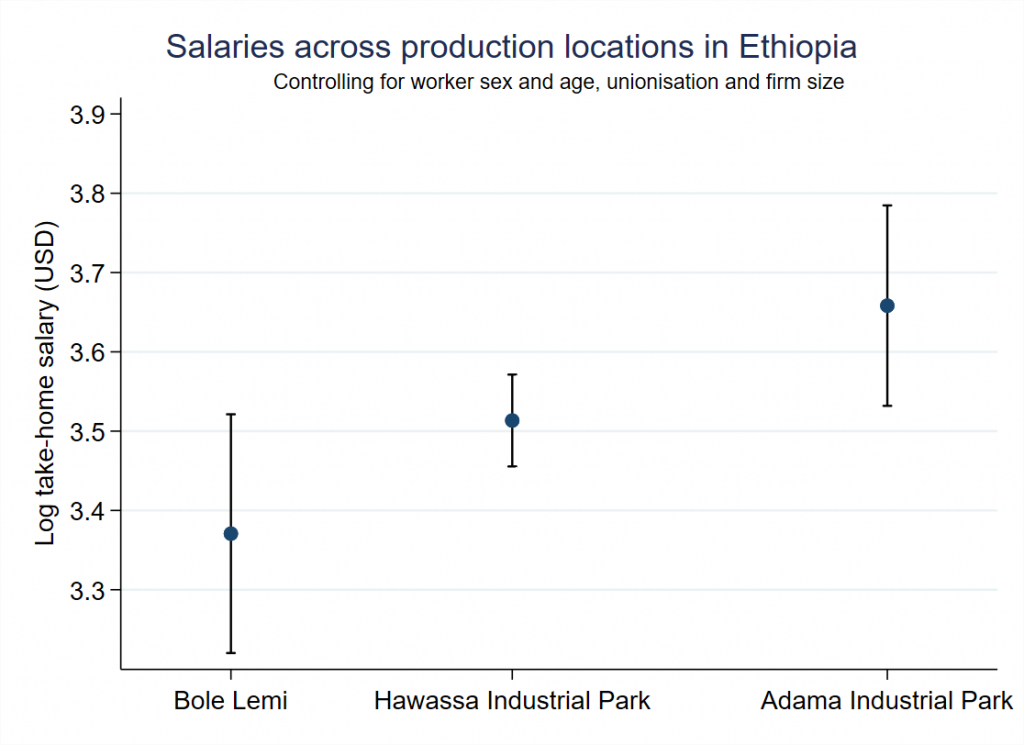

In Ethiopia, differences are less clear and at first glance at least less intuitive. Wages are lowest in Bole Lemi, which is just outside of Addis Ababa (the capital city), and highest in the industrial park near the much smaller city of Adama. The Hawassa Industrial Park, by far the most important apparel production centre in the country, occupies an intermediate position. While there are large differences in the point estimates across locations there is substantially greater variation in wages in each location than in Kenya, meaning that most differences in Ethiopia are not statistically significant.

Figure 2. Salary differences by location in Kenya and Ethiopia

How can we explain these differences?

To understand the reasons for this variation we need to look at differences in labour market institutions between the two countries, and at the extent to which workers in each location have been able to use local labour market conditions and collective agency to their advantage.

Let’s start with Kenya. In Kenya, workers have a degree of institutional power due to laws on minimum wages and high levels of unionization. Annual wage increases in all firms are driven by shifts in the national minimum wages. In part, this helps explain the higher overall wage level. However, differences in wage levels across production locations appear to be determined by workers’ marketplace bargaining power, that is, by the extent that workers are easily able to find a new job. In Athi River, living costs are higher and alternative jobs are more available, thereby driving up reservation wages. On the other hand, in the areas outside of Mombasa workers have few other job opportunities, meaning they have less marketplace bargaining power and are more likely to accept lower wages.

By contrast, Ethiopia has no national minimum wage, and unionization is too recent to have had an impact. Our explanation focuses on associational power, that is the power that workers gain from joining together in collective struggles, and from developments and regional differences in state-labour relations. The ‘older’ industrial parks such as Bole Lemi and Hawassa had very low initial wages rates, which slowed down subsequent wages growth but also has been a key driver of conflict in the parks. For example, Hawassa Industrial Park has seen the most industrial action and the politicization of strikes, which over time led the government to lean on firms to make concessions. In the Bole Lemi Industrial Park, we would expect to see higher wages due to its proximity to the comparatively higher-wage economy of Addis Ababa. However, firms seek to counter this pressure by investing considerable resources to source workers from the surrounding peri-urban area. The comparatively higher wages levels in the Adama Industrial Park are the result of both worker agency and the fact that this park was the last to become operational. The park saw intensive labour activism as apparel supplier firms were setting up in the new industrial park, and the supplier firms corrected for low wages rates paid in the older parks to attract and maintain workers.

What do these findings tell us about the outlook for apparel workers seeking higher wages?

In both Kenya and Ethiopia, workers’ marketplace bargaining power has decreased because of recent crises. Demand for apparel products in key end markets, especially the US, has slackened in recent years due to the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic and increased competition from the ultra-fast fashion sector, leading to order losses in both countries. In Ethiopia, this was exacerbated by a civil was that led to the loss of preferential access to the US market. Both countries have seen worker layoffs and factory closures (even as some factories moved from Ethiopia to Kenya).

Our finding that differences in wages in apparel assembly factories are driven less by differences between companies and more by variation in local labour market conditions and worker power suggests that while worker power can achieve limited results, worker power is unlikely to improve in a world where global buyers can set ceiling prices for apparel suppliers.

The full paper presenting the analysis is coming, so stay tuned!

Florian Schaefer is a lecturer in international development at King’s College London.