By Yvette Ruzibiza and Simon Turner

Tanzania used to be commended internationally for its generous refugee policy, since the 1960s hosting forcibly displaced people from war-torn neighboring countries including Burundi and Rwanda, and actively supporting anti-apartheid freedom fighters from southern Africa. This image has, however, changed significantly in recent years. Tanzania is now using restrictive policies and rhetoric to deter refugee arrivals and encourage some of those in the country to repatriate.

The shift started in the late 1990s, after large influxes of refugees from Burundi, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), and Rwanda. The Refugees Act of 1998 marked the beginning of the end of the country’s generous reception policy. In 2018, Tanzania withdrew as a signatory to the Comprehensive Refugee Response Framework, a precursor to the Global Compact on Refugees, and said it would discourage the arrival of new asylum seekers. “Go back to your home,” then-President John Magufuli told Burundian refugees the following year. “Don’t insist on staying in Tanzania as refugees or expect citizenship while Burundi is now stable.” The government has prohibited or restricted refugees living in camps from working and generating income, making life there harder by closing markets, among other actions. Since 2017, more than 145,000 Burundian refugees have returned to their origin country voluntarily, although rights groups have alleged many were intimidated and pressured to go back. And in 2021 Tanzanian authorities were accused of forcibly returning thousands of people to Mozambique.

What has driven this move to a more restrictive policy, and what have been the effects on the ground? The change has manifested in both official policy and in some cases social relations between refugees and host communities, though some natives and migrants in border areas tend not to share the animosity that government policy would suggest. Restrictions have also not been totally effective at containing refugees in camps but have nonetheless kept many unauthorized migrants in the shadows, out of fear of encountering authorities. Based in part on interviews with refugees, other migrants, and Tanzanian natives near the Tanzania-Burundi border, this article examines the policy transition and its repercussions.

Refugees in Tanzania

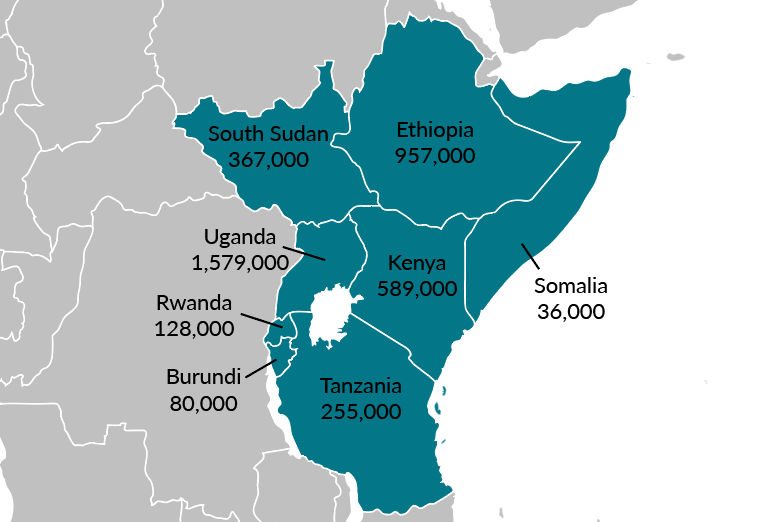

More than 255,000 refugees and asylum seekers lived in Tanzania as of June 2023, according to the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Approximately two-thirds of them are from Burundi, where the government has violently cracked down on political opponents, and one-third from the DRC, where armed groups regularly battle over land and natural resources in the east. Most forced migrants live in Tanzania’s northwest, particularly in the Nyarugusu and Nduta camps (home to about 83 percent of refugees in Tanzania) and in nearby villages (9 percent) and settlements (8 percent). Just 0.1 percent live in urban centers. Fifty-five percent are children under age 18. Notably, these are figures from a time when Burundi and DRC have experienced relative calm, meaning the estimates represent the lower range for recent years.

Compared to other East and Horn of Africa countries, which combined hosted 4 million refugees and asylum seekers as of mid-2023, Tanzania’s refugee population is small. Approximately 1.6 million refugees and asylum seekers lived in Uganda as of July, and 589,000 were in Kenya as of March.

Figure 1. Refugee Populations in East and Horn of Africa Countries, 2023

Source: UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), “Operational Data Portal: Regional Bureau for the East and Horn of Africa, and the Great Lakes Region,” updated August 3, 2023, available online.

Drivers of Tanzania’s Changing Approach

Humanitarian arrivals in Tanzania increased dramatically in the 1990s due to political unrest and ethnic conflict in Burundi (starting in 1993), the genocide in Rwanda (in 1994), and the war in Zaire/DRC (starting in 1997) (see Figure 2).

Refugee Fatigue and Scarce Support

In particular, hosting refugees from the Rwandan genocide strained Tanzania’s capacity, beginning to set the conditions for the country’s later cooling policy responses and attitudes.

Over just 24 hours in April 1994, an estimated 100,000 refugees crossed the Rusumo bridge into Tanzania. While international groups and partners delivered astonishing assistance in a remote and poor part of Tanzania, the massive influx nevertheless created challenges at various levels.

Figure 2. Refugees and Asylum Seekers in Tanzania, 1961-2022

Source: UNHCR, “Refugee Data Finder,” accessed July 14, 2023, available online.

First, as global media attention drifted away from the Rwandan genocide and its effects, international support for Tanzania’s refugee response dwindled. Donor support remains a challenge today. As of June, UNHCR had just one-quarter of the $115.9 million it estimated necessary for operations in Tanzania in 2023, more than half of which came from a single donor: the United States. Due to funding limitations, the World Food Program this year reduced the amount of food assistance it provides refugees in Tanzania, offering just half the minimum daily calorie requirement. Certainly, Tanzania is not alone in this trend. In June, UNHCR reported having secured funding for just 32 percent of its $10.8 billion global budget for 2023.

Refugees as Threat to National Security

The 1990s increase in refugees caused security concerns at the national level, although it is unclear whether they stem from genuine fears or were influenced by populist calls for increasing vigilance. In either case, refugees are seen as a security threat at three levels. First, the government is concerned that large numbers of foreign nationals—some of whom have been engaged in genocide and violent conflict—will pose a security threat. Furthermore, government officials have suggested that refugees in Tanzania can cause diplomatic tensions with the neighboring states from where the refugees come. In other words, Tanzania may be accused of harboring rebels. Thus, the government has agreed with the government of Burundi to encourage the repatriation of Burundian refugees. Finally, the significant presence of international and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) in western Tanzania challenges the sovereignty of the Tanzanian state in these regions, prompting additional anxieties for the government in Dodoma.

Encampment Policies

One manifestation of the stricter approach taken towards refugees in recent years is the enforcement of a strict encampment policy and a gradual tightening of livelihood opportunities in the camps. Any refugee arriving in Tanzania must register with the Tanzanian Red Cross and be transferred to a refugee camp. The camps are located far from any major towns, and for new arrivals, this approach can mean limited contact with the rest of society.

Refugee camps are bursting, and residents are not allowed to leave to work, trade, or go to school. This policy of containment isolates refugees from the rest of Tanzania’s population, severely impacting their livelihoods and trade. This situation sharply contrasts with the past (such as during the time of Tanzanian founder Julius Nyerere), when the Ministry of Home Affairs officially considered refugees “resident guests.”

Another sign of the transition from a welcoming stance to the common current portrayal of refugees as a burden for the nation is the push for Burundian refugees to leave, despite unresolved problems in their homeland that were at the roots of their asylum requests. Leaders such as Magufuli, however, have asserted that Burundi is safe to return to, and have actively tried to encourage repatriation. As part of this move, the Ministry of Home Affairs has restricted refugees’ movement beyond the camps more than in previous years, closed some markets in the camps, and banned camp residents from nurturing gardens.

It appears; however, the policies are not necessarily deterring refugees. Despite the return of 145,000 Burundian refugees since 2017, even more remain in Tanzania, and new arrivals have come recently from DRC. In just a few days in March 2023, for instance, more than 2,600 Congolese arrived in Tanzania, fleeing violence in the Kivu region. Furthermore, it is common knowledge that, despite the travel restrictions, refugees regularly leave the camps, either to work as farm laborers for Tanzanians in neighboring villages or for longer periods of time to try their fortune in Kigoma and other towns.

Box 1. Research Methods

This article is based in part on the authors’ ethnographic research in Kigoma town and surrounding villages in 2022 and 2023, as part of the Everyday Humanitarianism in Tanzania (EHTZ) project partly funded by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Danmark and administered by Danida Fellowship Centre under Grant Number 18-12-CBS.

The authors were denied access to Nyarugusu refugee camp for what authorities described as security reasons, and so shifted their focus to the many humanitarian migrants who live without authorization in and around Kigoma. As part of this research, they interviewed 35 Burundians, 27 Congolese, and 19 Tanzanians.

Realities on the Ground

The government’s restrictive approach towards refugees and other migrants tends not to be reflected in the attitudes of some Tanzanians, especially those near the border. While policies have prompted many humanitarian migrants to cross into Tanzania irregularly and remain without legal status, putting them in a vulnerable position, longstanding ties and interconnectivity defined the situation on the ground. Tanzanians and migrants alike told the authors that most arrivals are welcomed.

“My family doesn’t have much but we have been helping refugees whenever we can,” a Tanzanian woman in Kigoma said in an interview. “It doesn’t take much to help… it could be that a refugee came to you hungry, and you give him/her food.”

But some interviewees also talked about mutual mistrust. Tanzanians were afraid that Burundians especially were violent robbers, while migrants told many stories of being exploited by Tanzanians who threatened to take them to the authorities. A few Tanzanians substantiated these accounts of exploitation, expressing disapproval towards the behavior of some of their compatriots. These ambiguities seem to spring from the tensions that the restrictive policies create.

“Since I was once a refugee too, I’ve personally experienced this,” a fisherman of Burundian background with Tanzanian citizenship told the authors in Kigoma. “So, I know how it feels to be unwelcomed and how it can shrink opportunities… That is why I help refugees whenever I can… for example, in this fishing work that I do, I purposively give jobs to Burundian refugees or migrants.”

Sociocultural Ties along the Border in the Kigoma Region

The linkages between residents of Kigoma, which sits on the shores of Lake Tanganyika just 35 miles (55 kilometers) from the Burundi border, and Burundians tends to be very strong. Tanzania is an exceptionally ethnically diverse country, and many Baha people (of the Ha tribe) who live in Kigoma have close ethnic and linguistic connections to Barundi of Burundi. This situation is common in Africa, where colonial borders were arbitrarily drawn by European powers regardless of where different groups lived, splitting apart some ethnic communities and lumping others together with little regard for history. While this situation can be a driver of conflict in places such as Eastern Congo, where different groups were thrust into the same nation, it can also foster cross-border ties.

The Tanzania-Burundi border tends to be porous. Because people share major components of language and culture and have intermarried over centuries, it can be an impossible task to separate Tanzanians from Burundians and others based solely on appearance. Many migrants arrived during previous eras and simply became part of the fabric of the city. In fact, it is impossible to determine the exact number of Burundians and Congolese who have settled in Kigoma in recent years. Many arrive without authorization but can effectively avoid detection by speaking Kiswahili instead of their native languages. Still, the Burundians, Congolese, and Tanzanians who spoke to the authors all had stories about being able to tell the difference between Tanzanians and migrants, such as by the way they speak Kiswahili and their general behavior. For instance, Congolese in Kigoma said they would teach newcomers to not be so loud and flamboyant, so as to avoid attention and suspicion.

Economic Contribution and Exploitation

Many Tanzanians in Kigoma know and appreciate the economic value of incoming migrants. The most cited examples during interviews were about immigrants’ social and economic contributions, such as the Congolese music that is well known in Kigoma and indeed the rest of sub-Saharan Africa. Congolese musicians light up the town’s social scene and have revived the entertainment industry. It is the dream of many nightclub owners in Kigoma and across Tanzania to treat their guests to the pulsing sounds of performers with roots in DRC. When these musicians do well, they are considered Tanzanians. This was the case, for instance, with Nguza Viking, popularly known as Babu Seya, who was considered a successful Tanzanian singer in the early 2000s, at the height of his popularity with the release of the hit album Seya wa Mivalo. Yet he immediately reverted to Congolese status in the public consciousness when he was jailed in 2004 for child sexual abuse. (Viking and his son Johnson Nguza were pardoned along with more than 1,800 others by Magufuli in 2017.)

Burundians, meanwhile, described in interviews how they are known for their good work ethic, especially in farming and business. They are thus useful in the villages where they are utilized as a source of cheap labor. Those without authorization live outside the camps and are vulnerable to being exploited under the threat of being reported to the authorities.

All in all, Tanzanians and migrants alike said most foreign nationals were seen as a welcome addition to the socioeconomic life of the Kigoma region and Tanzania as a whole.

Discrimination and Criminality

Still, many Burundians face discrimination, particularly when compared to Congolese. During arguments between Tanzanians, it might be common for one person to label the other Burundian, as a way to accuse them of being a criminal, one respondent told the authors. Due to recurring conflicts in Burundi, Tanzanians have painted a caricature of Burundians as being armed and dangerous, typically making them the first suspect in every crime. Partly this is a result of the government’s attitude towards refugees, which trickles down to Tanzanian nationals. But to be fair, there have been cases of Burundians being involved in robberies and other crimes.

Yet some Tanzanians were sympathetic toward the newcomers, suggesting their country also deserved criticism for taking advantage of migrants and trapping many in vulnerable positions. In this line of thinking, authorities’ approach to forced migrants discourages many from seeking legal status, confining them to the margins and making crime more attractive.

Refugees Helping Refugees

Relations between migrants, meanwhile, tended to be positive. Generally, refugees have responded to their situation by helping one another and forming networks that assist new arrivals. Earlier arrived migrants typically host newcomers, who tend to be less proficient with Kiswahili and benefit from their more established guides and spokespeople. Settled immigrants also play a crucial role in orienting newcomers to the norms of their new society, offering guidance and protection from the possible danger of arrest or exploitation.

The Unintended Effects of Restrictive Refugee Policies

The Tanzanian government’s anxiety about refugees and other forced migrants is not uncommon. A restrictive stance on refugees and other vulnerable migrants has become common for governments in the Global North, such as Australia, the European Union, and the United States. But policies in the developing world—where the vast majority of refugees live—have tended to receive less attention. In Tanzania, the government has had to balance its obligations to new migrants with concerns about diplomatic relations with neighboring states, negotiations with large international organizations, and concerns about national security.

Interestingly, however, restrictive policies have yielded some outcomes that seem quite different from what was intended. Tanzania has clearly sought to deter the entry of new forced migrants and encourage the return of refugees, particularly to Burundi, arguing that they are a security threat and a burden on the local economy. Yet the authors’ research found that some of the local community in the Kigoma region did not fully share these assessments. While rumors and stereotypes about criminal Burundians did circulate locally, some Tanzanians saw Burundians and Congolese as economic assets, providing labor, business opportunities, and a market for local products. Further, the government’s policies have not caused all refugees to return, nor have they prevented them from leaving the camps. On the contrary, the increasingly harsh living conditions within the camps prompted many refugees to leave to, as they described it, “search for life” in neighboring villages and Kigoma town.

Although government policies do not reflect the attitudes of some local Tanzanians—and may at times be counterproductive—they are still impactful. Yet some effects may be unintended. Unauthorized migrants often fear being caught by the authorities, and Tanzanians fear they will be punished for assisting them. This means that Tanzanians who want to assist migrants tend to be exceedingly cautious and suspicious of engaging with them. Likewise, migrants are often afraid their Tanzanian hosts will turn on them and report them to authorities.

In other words, the attempted containment of refugees and asylum seekers has the effect of creating a general atmosphere of mutual suspicion between hosts and migrants, even while both sides acknowledge they have some degree of interdependence. As Tanzania narrows its open door to refugees, these relations may continue to deteriorate.

Yvette Ruzibiza is a postdoctoral researcher at Copenhagen Business School, in Denmark. She holds a PhD in anthropology from the University of Amsterdam.

Simon Turner is a Professor of social anthropology at Lund University, in Sweden. He holds PhD, master’s, and bachelor’s degrees from Roskilde University, in Denmark.

This is a repost of the Article: “Tanzania’s Open Door to Refugees Narrows” by Yvette Ruzibiza and Simon Turner that was first published on August 24, 2023, on the website of the Migration Policy Institute: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/tanzania-refugee-policy