By Stefano Ponte, Christine Noe, Dan Brockington, Opportuna Kweka, Rasul Ahmed Minja, Robert Katikiro, Faraja Namkesa, Mette Fog Olwig, Pilly Silvano, Ruth John, Kelvin Kamde, Lasse Folke Henriksen and Caleb Gallemore

The issue

New and more complex partnerships are emerging to address the sustainability of natural resource use in the Global South. These partnerships variously link donors, governments, community organizations, NGOs, firms, consultancies, certification agencies and other intermediaries. High expectations and many resources have been invested in these initiatives. Yet, we still do not know whether more sophisticated organizational structures, more stakeholders involved, denser social networks and more advanced participatory processes have delivered better sustainability outcomes, and if so, in what sectors and under what circumstances.

The research project

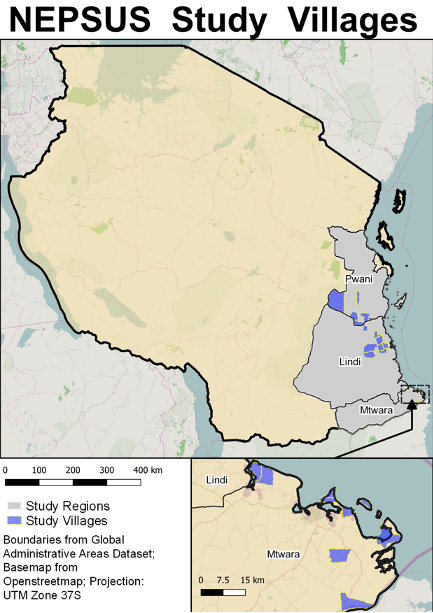

To fill this knowledge gap, the collective research project New Partnerships for Sustainability (NEPSUS), funded by FFU [1], assembled a multidisciplinary team to analyse sustainability partnerships that seek to combine conservation and development objectives in three key natural resource sectors in southeast Tanzania: wildlife, forestry and coastal resources. Researchers from Copenhagen Business School, the University of Dar es Salaam, the University of Sheffield and Roskilde University undertook five years of research, which involved carrying out a total of 331 key informant interviews, 81 focus group discussions, a survey with 1019 respondents, participant observation, and the collection of secondary documents, statistics, remote sensing and social network data.

In each of these sectors, we assessed whether co-management with local communities and private and civil society actors, and putatively more participatory processes in the governance of natural resources, result in positive environmental outcomes and improved livelihoods. We compared institutionally ‘more complex’ partnerships to relatively ‘simpler’ (more traditional top-down and centralized) management systems – and to ‘control’ locations where there are no partnerships in place.

We also assessed network complexity – as actors can use social networks to share their experiences, values, interests, knowledge and resources, but also to facilitate resource exchange and handle possible tensions. At the same time, networks may survive only when the most powerful and influential members of a partnership keep them alive, thus possibly reinforcing existing power imbalances. Our interest was to assess whether partnership complexity (in its institutional and network aspects) affects the ability to deliver sustainability outcomes.

Main findings

Legitimacy

Despite deliberate, evolving and persuasive efforts to raise awareness on the relevant rules and regulations, sustainability partnerships have struggled to gain and maintain legitimacy. Local communities are yet to perceive these partnerships as responsive, accountable and trustworthy arrangements that strike the requisite balance between community welfare and conservation goals.

Communities living in forestry sites perceived relatively higher levels of socio-economic and environmental outcomes accruing from new partnerships than their counterparts in wildlife and coastal resource sites. Lack of material incentives in wildlife partnerships and coastal partnerships limited their legitimacy in the eyes of local communities. Fishers and consumers of bush meat were affected by access restrictions, and alternative livelihood activities failed – or their benefits went to a small number of wealthy investors.

Complexity

We expected network complexity to correlate positively with institutional complexity, as the latter often entails participation of, and coordination between, a wide set of stakeholders. We found that there is a statistical association between these two dimensions (although it is highly sector-dependent), and that the building of more complex networks tends to predate the joining of more complex institutional governance forms. We interpret this as an indication that network building needs to be part of the initiation process of these partnerships.

Environmental impacts

The analysis of our remote sensing data suggests that there is a positive relationship between a higher degree of both institutional and network complexity and the maintenance of forest cover (in relation to forestry, wildlife habitats, and mangroves). However, we found no consistent relationships between either form of complexity and the perceptions by survey respondents on local environmental change.

These findings indicate that there is some potential for (institutional and network) ‘more complex’ forms of sustainability partnership to support effective natural resource management. But institutional complexity does not simply emerge on its own. It must often be deliberately constructed and maintained and it involves previous work building complex networks.

Impacts on livelihoods

Most people in the study sites we researched are farmers. Their livelihoods will improve to the extent that their farming revenues increase, and this happens mainly in relation to improved transport arrangements and farm-gate prices. New sustainability partnerships need to support farming activities if they are to bring prosperity. New partnerships on sustainability matter. They can make laws more just and fairer. They can introduce new business opportunities. They can safeguard natural resources more effectively. But they are not likely to be engines of large-scale prosperity of agricultural communities.

Cultivating Partnerships

Instead of decentralization, we are witnessing accountability transfers that move obligations to local authorities without sufficient resources allocated to them to carry out their tasks. In the contexts we examined in southeast Tanzania, we observed a multiplication in the number and variety of actors engaged in sustainability partnerships. These actors often represent different interests, express different world views and bring with them specific hopes, expectations and claims. Smaller and weaker actors – especially those who do not have capacity, organizational skills, and resources to participate as equals in partnerships – have been marginalized in decision-making.

We also see that the functional quality of sustainability partnerships in Tanzania depends on how they are embedded in networks of actors and institutions. To some extent, we have shown that social networks can act as potentially positive mediators of collective action coordination and collective learning processes.

Sustainability partnerships have been more inclined towards the provision of training on conservation issues than the development of alternative livelihood activities. As a result, they have had limited effects on socio-economic and livelihood outcomes, especially at the household level. They have thus failed to strike a balance of conservation and socio-economic outcomes, with the partial exception of community-based forest management. This has culminated into significant levels of community dissatisfaction with their performance.

Policy recommendations

1) Local community governance needs to be strengthened to improve a sense of ownership and increase cooperation and trust.

2) The income accruing from sustainabitlity partnership activities need to be distributed evenly and in a transparent manner, no matter how small.

3) Duplication and unclear division of labour among different actors and jurisdictions need to be addressed.

4) Long-term consistent financial support is essential.

5) The government and collaborating actors should provide clear economic incentives and support community-based enterprises.

6) When access to resources is tightened, it is essential that alternative sources of livelihood that make sense to local communities are facilitated.

7) Efforts should be made to facilitate contacts between local communities and other key actors before the establishment of sustainability partnerships and maintained during their operation.

For more information, see www.nepsus.info

Keep an eye open for the forthcoming open-access book: Stefano Ponte, Christine Noe and Dan Brockington (eds) Contested Sustainability: The Political Ecology of Conservation and Development in Tanzania. James Currey.

[1] The Consultative Research Committee for Development Research (FFU) is a programme committee that advises the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark regarding Danida’s support to development research.