By Jacobo Ramírez

Juchitán de Zaragoza, November 16, 2025

I grew up hearing that the Isthmus of Tehuantepec is a land of strong winds and even stronger wills. That idea always felt true, but only in recent years have I understood that this strength lives not only in the Zapotec history of territorial defense: it also lives in the bodies and lives of those who challenge, every day, the limits imposed by coloniality. Among them are the muxes.

When I arrived in Juchitán to accompany the 50th anniversary of Las Auténticas Intrépidas Buscadoras del Peligro, I understood that muxeidad is not just an identity category: it is a way of walking through the world, grounded in relationships with community, memory, ritual, and territory. Muxes inhabit a social and spiritual space shaped by Zapotec cosmology and by the colonial wounds that attempted to silence the gender plurality that existed long before evangelization.

Anthropological records speak of Aztec priests who wore clothing associated with another sex, Maya deities with multiple bodies, and ritual figures embodying duality and fertility. But those references, useful as they are, do not capture what it feels like to stand inside the church of San Vicente Ferrer and watch the muxes enter in their Tehuana dresses, carrying resplandores that illuminate centuries of resistance.

On that November 16th, as I watched them walk in, I realized I was witnessing something nearly impossible anywhere else in the world: a formal Catholic ritual dedicated explicitly to a third-gender community. An improbable gesture within the canon of a Church that has historically policed bodies and disciplined difference. Yet in Juchitán – as in so many Indigenous territories – imposition was never total. Here, Catholic faith was negotiated, reinterpreted, resisted, and at times transformed from within.

As the muxes advanced down the central aisle, accompanied by Maya representatives from Yucatán who also belong to Mesoamerican non-binary gender traditions, I felt history fold onto itself. It was as if precolonial traces and colonial wounds touched for a brief moment, revealing the persistence of worlds that never disappeared.

The priest spoke of justice, perseverance, and peace. He evoked the parable of the widow who insists before an indifferent judge, reminding us that those who seek justice often find doors closed. I heard his sermon not only as a spiritual message but as a living metaphor for what it means to be muxe in a country where gender, violence, and inequality intersect daily. At that altar, the Bible and everyday life seemed to speak to each other as equals.

After the Mass, a local band accompanied the procession toward the mayordoma’s home. The streets of Juchitán filled with music, sones, laughter, and steaming Oaxacan mole served in deep clay bowls. We were also offered fresh hibiscus water, and, as tradition holds, we gave a cash donation to the mayordoma – a communal gesture that reminds us that every celebration, every vela is sustained by an economy of care, daily labor, and collective commitment.

From my anthropological perspective, but also from my position as a person with Isthmus roots – child of parents born in this territory – returning to learn, I understood the political depth of that ritual. What happened that afternoon was not simply a Mass: it was a declaration. A statement that Indigenous worlds persist beyond attempts at colonial normalization. A living expression of ontological plurality. A bodily and spiritual resistance to the imposed gender binary.

For centuries, muxes have sustained community life in the Isthmus: they organize velas, care for their families, work in the markets, and keep alive the affective and ritual networks that uphold Zapotec existence. They are central to social reproduction, though their contributions rarely fit the economic and administrative categories defined by the State. Their labor is relational, situated, vital, and deeply feminized. And like so many forms of feminized labor, it is profoundly undervalued.

This Mass, this crossing of the Indigenous and the Catholic, of colonial wounds and everyday creativity, illuminates the contradictions that muxes inhabit without seeking to resolve them. From within ambivalence, they transform the systems that once excluded them. Through the aesthetic work of the body, they weave historical continuity. From the margins, they open futures.

I remember walking behind the procession, thinking about the way muxe testimonies overflow any fixed category. They do not seek to explain an identity; they assert a presence: they exist from within a world where ritual, care, and resistance are deeply intertwined. They told me – between laughter, makeup, pain, memories, and pride – that being muxe cannot be translated into Western categories; it is a relationship, a mode of community-making, a way of sustaining social life in the face of persistent coloniality.

This blog emerges from that moment: from a Mass that not only celebrated fifty years of history but revealed a continuity far older. From the understanding that muxes are neither folkloric symbols nor tourist postcards: they are living testimony of how Indigenous peoples create worlds at the margins, reinvent what they inherit, and challenge what was imposed upon them.

It is in that territory – fractured, vibrant, contradictory, and profoundly human – that the testimonies I share here are born. Each one is a situated intervention, a form of future-making that pushes its way through the winds of the Isthmus.

Final Note

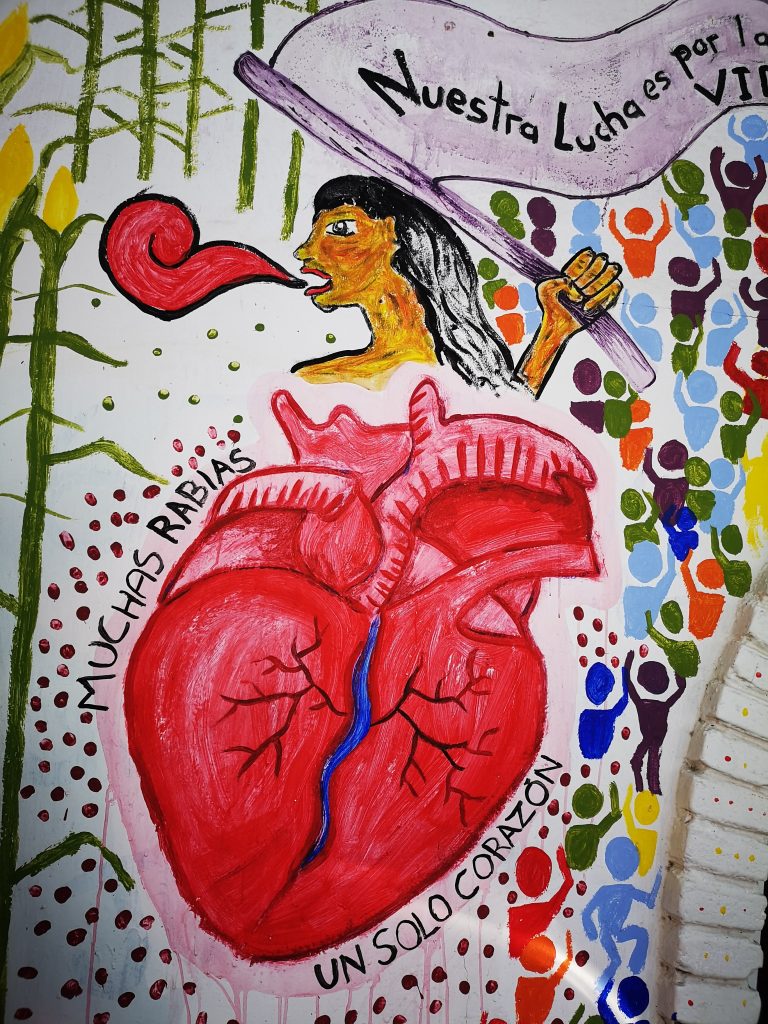

The photographs included in this blog were taken by me, in an effort to capture not only the moments but also the strength and presence of those who made this celebration possible. Everyone portrayed granted verbal consent for the publication of these images, which aim to honor their stories and their journeys.

I extend my deep gratitude to Felina Santiago Valdivieso, Kika Godínez, Amurabi Méndez, Eduardo López Castillo, Patricia Castillo Luna, and Torben Laurén for their accompaniment, their care, and their supportive presence during the Vela of Las Auténticas Intrépidas Buscadoras del Peligro. Their support made possible not only this visual record but also the collective experience that sustains it.

Dr Jacobo Ramírez is an Associate Professor at the Centre for Business and Development Studies (CBDS) at Copenhagen Business School (CBS). His research focuses on organisational strategy in fragile states and other complex institutional environments shaped by security risks, displacement, and social unrest. His current work examines renewable energy investments in emerging markets. A Mexican–Danish dual national, Jacobo was born in Mexico and has lived and worked in Copenhagen since 2006.