By Daniel Brockington, Caleb Gallemore, Lasse Folke Henriksen, Ruth John, Kelvin Kamde, Robert Katikiro, Rasul Ahmed Minja, Faraja Namkesa, Christine Noe, Mette Olwig, Stefano Ponte, and Pilly Silvano

Bricolage, open and slow project design, reflexivity and conviviality can help addressing some of the unequal power dynamics that underpin collaborative research projects involving scholars and institutions from the Global North and Global South.

Introduction

In this ‘Business & Development’ blog contribution, we (a group of researchers, some based in the global South and some in the global North) reflect upon our experience in collaborating on a relatively large research project on conservation and development in Tanzania (New Partnerships for Sustainability, NEPSUS). We wish to reflect upon the structural inequalities embedded in these kinds of collaborations and on how ‘bricolage’ (including ‘open’ and ‘slow’ design features) can be used to alleviate at least their most problematic manifestations. We present our reflections along two main lines: (1) through a ‘cleansed’ approach, where design and methods are presented as devoid of power dynamics and structural inequities, failures and adjustments, and following the execution of a clear plan and milestones (what we often read in journal articles and final reports of research projects); and (2) a ‘bricolage’ approach including all the aspects, joyful or problematic as they may be, that are usually omitted from the cleansed approach. The first part of the discussion will appear very familiar to the reader, as we follow the canon of ‘legitimate’ scientific inquiry; in the second part, we provide a series of reflexive vignettes from the participants of the project, which are meant to open up the Pandora’s box of trials and errors, the tribulations of open design, unexpected successes and failures, and the importance of time spent making mistakes together and learning from them.

If you are interested in knowing more about the results of the project, see our edited book Contested Sustainability (available in open access here).

Genesis of the project

In July 2014, the conference ‘The green economy in the Global South’ took place at the University of Dodoma (https://greeneconomyinthesouth.wordpress.com/hosts-and-organisers/). Organized by a network of institutions in Tanzania, South Africa, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, and Denmark, it brought together over two hundred scholars and included over sixty papers and presentations. On the margins of the conference, a group of Tanzanian and European researchers (some of whom are co-authors of this piece) started informal conversations and critical reflections on what the ‘Green Economy’ was really about, whether it was making a difference to people and nature in global South contexts, and whether the veritable explosion of ‘sustainability initiatives’ was worth all the hype. Some of these scholars, broadly involved in the political ecology and political economy fields, were particularly interested in understanding the power dynamics of ‘participation’ and ‘decentralization’ that have come to characterize conservation and development initiatives, their legitimacy in the eyes of the communities that they were supposed to empower, and whether they are positively impacting local livelihoods and natural resources.

The ‘Green Economy in the South Conference’: University of Dodoma, July 2014

A smaller group of scholars from the University of Dar es Salaam, the University of the Western Cape, CIFOR (Nairobi), Copenhagen Business School (CBS), Roskilde University, and the University of Sheffield then met in Copenhagen (with funding from CBS) in 2015 to further discuss these issues in view of attempting to secure funding for a research project. This group included what were to become the two co-PI of the project (Christine Noe and Stefano Ponte). Out of this workshop arose a more specific focus on trying to understand why sustainability partnerships, and especially those combining conservation and development objectives (a specific interest of Christine), were becoming increasingly ‘complex’ – and whether this complexity was paying off in terms of better inclusion, legitimacy, and indeed socio-economic and environmental outcomes (a specific interest of Stefano). The idea for the New Partnerships for Sustainability (NEPSUS) project came out of these reflections and led to the development of a comparative design (covering three natural resource sectors that are key to Tanzania – wildlife, forestry, and coastal resources), a regional focus (on southeast Tanzania) and an interdisciplinary approach (involving scholars from the fields of geography, political science/political economy, sociology, and development studies). NEPSUS eventually received funding from the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 2016 (Consultative Committee for Development Research, Royal Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Grant 01-15-CBS).

The pitch

We received funding on the basis of the following argument: new and more complex partnerships are emerging to address the sustainability of natural resource use in the Global South. These partnerships variously link donors, governments, community-based organizations, Non-governmental Organizations (NGOs), business, consultants, certification agencies, and other intermediaries. High expectations and many resources have been invested in these initiatives. Yet, we still do not know whether more sophisticated organizational structures, more stakeholders involved, denser social networks, and more advanced participatory processes have delivered better sustainability outcomes, and if so, in what sectors and under what circumstances.

Convivial activities during the one-month intensive stay at the start of the project: Copenhagen, August 2016

We assembled a multidisciplinary team to analyse sustainability partnerships in three key natural resource sectors in Tanzania: wildlife, forestry, and coastal resources. In each of the selected sectors, we sought to assess whether co-management with local communities and private and civil society actors, and putatively more participatory processes in the governance of natural resources, result in positive environmental outcomes and improved livelihoods. We wanted to compare these ‘more complex’ partnerships to relatively ‘simpler’, more traditional top-down and centralized management systems and to locations where sustainability partnerships are not in place. Within-sector comparisons allow a fine-tuned analysis that is cognizant of historical, location, and resource-specific issues, which can be used as input for resource-specific policy and partnership design. Comparison across the three different sectors allow the identification of possible common experiences and lessons that can be applied to natural resource governance more broadly.

Tanzania, we argued, is an ideal case to examine these issues because it has implemented several policy reforms involving new forms of partnerships in these sectors. Tanzania is considered an important case study of decentralization and participatory approaches in the management of wildlife, forestry, and coastal resources. This is because, unlike other countries in eastern and southern Africa, Tanzania does not have the problem of defining what is a ‘community’ in participatory natural resource governance. The Local Governments Act (1982, Decentralization) provides a legal definition of a community: a village. Hence, decentralization goes all the way down to the village level, unlike in other countries where the meaning of community has remained contested. Yet, the implementation of what is stipulated in the numerous policies and laws remains conflictual and contested in all three sectors we examine. The role of these new partnerships is highly significant, particularly given the proliferation of initiatives related to REDD+ and the co-management of wildlife, coastal resources, and forests – and their tourism-related sustainability components.

Design and methods: The sanitized version

Resource selection

We examined three natural resource systems (wildlife, forestry, and coastal resources) that are central to any measurements of sustainability. Tanzania provides an ideal case because these three resource systems are managed under different partnership arrangements. Using all cases from one country reduced variation in government contexts and frameworks. Moreover, all cases from the same country shared a similar evolution from centralized to putatively decentralized management approaches that emerged around the same time (in the late 1990s). While the case studies differed in specific resource types and particular actors involved, there are several similarities across sectors that allow for meaningful comparison, such as the normative complexity of the objectives of the partnerships. All cases sought to attain both environmental and livelihood outcomes, while improving natural resources governance at the local level. In each resource type, we also sought to minimize variability by selecting sites that are relatively comparable in terms of socio-economic and agro-ecological factors.

All three sectors we selected in Tanzania have by now established traditions of:

- ‘simpler’, more centralized and top-down conservation initiatives, such as game reserves, forest reserves controlled by central or local governments, and marine parks; and

- ‘more complex’ partnerships (see discussion below) that are based on different degrees and forms of co-management and involve more stakeholders: Wildlife Management Areas (WMAs); combinations of Community-Based Forest Management (CBFM) with timber certification and REDD+ initiatives; and Beach Management Units (BMUs).

Site selection

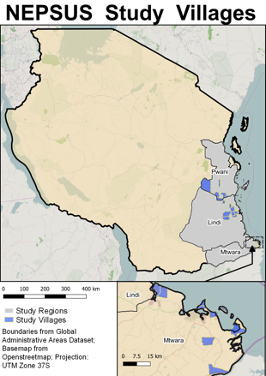

We selected the macro-region of southeast Tanzania for the following reasons:

- The different resource types are located in contiguous areas that are, in the context of nationwide variation, agro-ecologically and socio-economically similar. All are coastal regions at a similar latitude and with similar topography, with livelihoods that depend largely on farming.

- This region hosts simpler partnerships for all the resources studied: various National Forest Reserves in Kilwa, the Selous Game Reserve in Rufiji, and the Mnazi Bay Ruvuma Estuary Marine Park (MBREMP) in Mtwara.

- The study sites are well-known for pioneering community participation in conservation for the respective resources studies (WMAs, CBFM, and BMUs), allowing us to assess partnership complexity and compare across resources.

This broad study region was divided into study sites in three different districts, each characterized by different types of natural resource governance. We selected Rufiji district in Pwani region because it hosts various WMAs that border the Selous Game Reserve. We selected Kilwa district in Lindi region to explore the formation and compare the performance of forest management partnerships. Kilwa has a well-developed CBFM program with FSC certification and REDD+ initiatives and has many organizations that are working to support local communities’ participation in conservation activities. Finally, we selected Mtwara Rural district in Mtwara region because it features two categories of collaborative fisheries governance, BMUs and MBREMP.

At the local level, villages were selected based on a preliminary complexity scoring that sought to identify simpler, more complex, and control sites. The different degrees of partnership complexitywere first determined ex ante to guide the identification of appropriate sites for fieldwork, through a combination of scoring that included: (1) the number of actors and actor categories involved in the partnership; and (2) the complexity of the institutional setup (decision-making system and degree of sharing of access rights). Following preliminary fieldwork that took place in February and March 2017 in Rufiji, Kilwa, and Mtwara, and a validation exercise with the NEPSUS Stakeholder Advisory Board in Dar es Salaam in April 2017, the site selection matrix was partially adjusted to reflect upon local realities.

Socio-economic data collection

NEPSUS employed a broad portfolio of data collection methodsthat the members of the research team have practiced over many years of work in Tanzania and elsewhere. The diversity of methods enabled critical reflection and triangulation of data. In total, we carried out 331 key informant interviews, 81 focus group discussions and a survey with 1059 respondents.

We carried out key informant interviews with representatives from key organizations to explore the history and current performance of different governance arrangements, the legitimacy of partnerships, and perceptions on the environmental and socio-economic outcomes of partnerships – as well as to map social and inter-organizational networks. In interviews, informants were also asked to fill in a roster of their peer network within the partnerships, detailing the strength of their social ties and the frequency of their interaction. We also included questions about organizational collaboration. In order to obtain a list of potential respondents a mapping of stakeholders was conducted, which provided an overview of various actors’ involvement in sustainability partnerships. Interview guides for key informants both at the national level and with individuals at the household level were developed for these purposes. Digital audio recorders were used to record the interviews if the informant granted informed consent.

We collected secondary data through a review of books, published scientific papers, journal articles, reports, permits, management plans, and unpublished materials to provide background information and complement information collected from primary sources. Other statistical information such as demographic and socio-economic profiles of the districts and villages studied were also collected across the three sectors.Some of the documents reviewed from district level stakeholders were reviewed under the condition of maintaining the providers’ confidentiality due to their sensitivity.

We convened focus group discussions in local communities to gather data on community narratives and perceptions of environmental and socio-economic change, and the history, dynamics, legitimacy, and impact of partnerships. The focus groups were organized in places of participants’ choice within villages and targeted groups included youth, women, and mixed groups. Participants were introduced to the purpose of the project and the objectives of the discussions.

A questionnaire-based survey was administered using ODK as the main method to gather data for quantitative statistical analysis of socio-economic outcomes at the household and community levels, perceptions of partnership processes and functioning, and perceptions of environmental outcomes. Households were selected through stratified random sampling to ensure proportional representation under different strata (male and female-headed households; different poverty/wealth ranks; household location in the village between near and far households). The questionnaires contained the same modules across resource types in order to compare outcomes, but also allowed for some adaptation to resource specificity. We employed a stratified random sampling to ensure spatial coverage that at least each sub-village had to be represented in the sample given local politics of resource governance and the importance of proximity to the resource. Since the project focused on local communities, the unit of analysis was the household. A total of 1,059 questionnaires were administered in 24 villages across the three resource sectors: Wildlife (353), Forestry (352); and Coastal resources (354).

The challenges of fieldwork: Rufiji, February 2017

We followed our study villages’ evolving position in social networks across four intervals covering the years up to, during, and following the introduction of new resource management systems (2000-04, 2005-09, 2010-14, and 2015-18). Deploying event- and document-based sampling strategies and respondent-driven link-tracing techniques, we collected social network data characterizing the network of organizations engaging in business, technical, and governance collaborations on issues related to the focal resource in our study villages and among key region- and state level governance bodies, as well as the connections between village governance organizations and these other actors. We coded all identified organizations into three mutually exclusive organizational types: government, private sector, and NGOs. We triangulated three information sources to identify these networks, collected during multiple fieldwork trips to the study sites.

Joint fieldwork: Mtwara, March 2017 and March 2018

First, all village visitors are obliged to sign the village guestbook, which records visits from corporations, NGOs, donors, and government officials. Consulting guestbooks as far back as those records were available in each village, we constructed initial lists of village collaborators. To fill in potential omissions due to missing guest books, recording lapses, or collaboration that did not involve direct village visits, we consulted policy and conservation project documents obtained from national archives, expert interviews, and online research. We used these materials to code time-stamped collaborative relationships, adding new organizations encountered to the list of village partners constructed from the guestbooks. Third, to verify collaborations and to identify the nature of the collaborative relationships, the team interviewed representatives from Village Councils and Natural Resource Committees about the organizational partners with whom they had collaborated on sustainable forest management. The existing list of organizations from the guest books and documents informed these interview questions, and we asked respondents to elaborate on the nature of specific collaborations and to identify further collaborators not yet on the list. Informants also provided details on the timing of collaborations according to the periodization outlined above.

Environmental data collection

NEPSUS’s intention to examine environmental change for aspects of forestry, wildlife, and coastal resources set an ambitious data collection agenda which we were only able to partly fulfil. The best data we collected were for changes in forest cover. Here we were able to get complete, precise, and accurate measures of change using a variety of remote-sensing techniques. We were not able to acquire actual wildlife counts for the study villages, so in this case we used measures of habitat change, and specifically habitat fragmentation, as a proxy for wildlife. This measure would capture the conversion of forest to farmland, and, hence, transitions from land which is more hospitable to wildlife to land which is less conducive to biodiversity. In relation to marine resources, we were again unable to acquire reliable data on fish stocks. However, we obtained accurate data on the condition of mangrove forests and on coral reefs from satellite data.

Training of satellite reference points for mangrove detection: Mtwara, March 2018

Behind the scenes

The sanitized version we provided above looks very impressive. We are proud of what we achieved, but the way this came about was an operation of bricolage. In the following ‘vignettes’, we wish to provide personal insights from a variety of perspectives on the trials and errors, the tribulations of open design, unexpected successes and failures, and the importance of time spent making mistakes together and learning from them.

NEPSUS according to Stefano (co-PI based in Denmark)

Unequal power dynamics are quite obvious in collaborative research projects involving individuals and institutions from the global North and global South. In our case, first of all, we applied to a Danish research fund, which also implied Danish accounting and reporting rules (an object of much frustration in Tanzania) and through a call focusing on specific themes developed by global North researchers and policy makers. Yet, carrying out a workshop with all participants to prepare the application together allowed priorities to be tweaked and reframed in ways that better aligned with the interests of Tanzanian researchers. I am familiar with the funding mechanisms in Denmark and knew how to design a project that had fair chances to be funded, but had no experience in conservation issues and limited knowledge of political ecology – a strong interest of Christine’s (and many others in the team).

Once funding was secured, we spent an entire month, full-time all together in Copenhagen to flesh out the project design. We were all over the place at the start, but eventually landed on what we thought would be a complex but relatively feasible design (later on, we chopped off a number of features that made it ‘really’ feasible). We followed up with an online meeting with our Academic Advisory Board and a full-day in person meeting with our stakeholder advisory board in Tanzania. After these meetings we changed the site selection fairly profoundly, given the quite fundamental mistakes we were making in some of our assumptions.

The project design and related methods were still based structured comparison at that time, bringing out a multidimensional view of conservation and development initiatives that necessitated sophisticated quantitative and qualitative data and analyses, but also went through a permanent act of bricolage. Bricolage with multiple methods did not detract from the robustness of the methods we employed, it added to it. We were able to collect high-quality qualitative and quantitative data that allowed us proper triangulation. We interviewed many people, but also collected remote sensing data. Working with software-supported qualitative analysis, social network analysis and statistical analysis of matching pairs was a special revelation and involved massive learning from all sides.

The rigour (and in some cases the computer power and time) involved in these triangulated methods were remarkable – and none of my making as a co-PI. The Danish statistical computing office (which provides computing power facilities and capabilities to all Danish research institutions) once called to ask us to run our models during the weekend, as during the week we were consuming too much computer power. These data analysis methods greatly improved the comparative dimension of the project but we learned how to apply them as we went along. During the regular research analysis workshops in Copenhagen, the ‘quant situation room’ was busy all the time (see vignette below), but they also often snatched the ‘qual people’ to train their models properly and identify possible mistakes and misrepresentations in data coding.

But most importantly, our collaboration involved shared meals, walks, relay runs, and much informal time together as a large group, and in more specifically focused teams, both in Denmark and in Tanzania. We also lost a number of collaborators along the way, as they turned to other priorities (one of them unfortunately passed away). Those who stayed worked together, shared ideas, intellectually sparred, faced challenges, socialized, and partied, had the occasional conflict, lost their hearts and/or patience, got tired, and became reinvigorated. We had ceremonies, celebrated holy days of various kinds and even went on large competitive running races. We did this at the early stage of the project as we were working on methods and study design, in the early stage of fieldwork as we tested those methods, and towards the end of the project as we analysed and wrote up the data. The result of these collaborations was that we gained a much better insight into each other’s data and methods, and the interpretation of those data, and shared mistakes openly in view of fixing problems. And eventually, writing itself (and the dedicated workshops and related resources) became part of the method of doing research.

In and around workshops and writeshops: Copenhagen, 2018 and 2019

We did not achieve all we set out to do, some of our results merely replicate what others had found already, and other findings pull in all sorts of different directions. But we also provided original insights, exciting new discoveries, and hopefully will inspire policy and project design. We have been surprised by our findings, and our understanding of places and processes we thought we knew has been challenged. We published in relatively good journals and edited a book – but process, not output, drove these activities.

The project took far longer than we had expected (this is not unusual), but mostly because we were continuously adjusting and recalibrating activities and spent much longer periods of time analysing data and writing together. Open and slow design features were thus important. We prioritized process first, and hoped to harvest of course (and we did), but did not focus on output itself until late in the project.

My lack of experience and knowledge on conservation and political ecology at that time allowed me to approach these topics and disciplinary fields with fresh eyes and curiosity, to seek learning and exercise some degree of humility. I could do that because I was leaning on other scholars (especially Christine and Dan) who are reference figures in these fields. Also, I could afford this approach because of my relative seniority in academia, privileged access to resources, and because I am employed in a multidisciplinary department where I have wide freedom on what journals to publish in (and where books are legitimate forms of output). This is a far more difficult terrain to manoeuvre in for younger scholars and for colleagues who are in monodisciplinary departments, especially in the global South – where mimicking global North norms of ‘quality’ often comes without the necessary resources and lightening of teaching loads.

Mood board at a writeshop: Dar es Salaam, 2023

The amount of funding was enough that we did not have to split hairs on expenditure, but not large enough to attract scholars simply ‘because of the money’. Many of our Tanzanian colleagues became part of the project because of a strong existing network built by Dan and Christine which I band-wagoned on, and because they wanted to expand their international publication profile. They engaged as academics, intellectuals and scholars – not simply as collectors of primary data or consultants. I benefited as much from their network and knowledge as they did from my access to funding possibilities and publication experience. We repeatedly went around to present our work by highlighting that we engaged in mutual learning (rather than the much abused term capacity building).

My long-term research engagement in Tanzania and fluency in Kiswahili brought down some barriers and avoided some forms of misunderstandings. Other times, it created problems. If I was so fluent in Kiswahili, why did I not know that a residence permit was necessary for any research stay (even a day) and not only a research permit and business visa – as immigration officers at a regional capital argued? Also, as a mzungu (white person), going to remote areas sometimes attracted unwanted attention that made research slower and more difficult; yet, carrying joint fieldwork is essential in starting to address structurally unequal North-South partnerships.

Tensions abounded and we all went through many unhappy moments and conflicts in the team – but we eventually clarified things or set more specific mutual expectations. Struggles over resources were rarely a question of money per se, but of the forms through which accounting and reporting needed to be done – something we had no flexibility about. These overall dynamics were not for everyone, and indeed a number of colleagues decided to step out of the project and focus on other activities. Still, they left an important imprint which we fully acknowledge elsewhere (see, e.g., the preface of our edited book).

NEPSUS according to Christine (co-PI based in Tanzania)

Transparency: I worked with astraightforward plain-speaking counterpart whose character shaped my role as coordinator of the project. While I consider myself of the same character, prior project management experience of the PI was crucial in dealing with complexity of a large (but also relatively young) team with different levels of research experience. There were tough times such as when the team was losing some key experts for different reasons or failing to get expected levels of commitment at the required time. These were precisely the learning moments which relate closely with patience and flexibility in leading a large team where everyone’s opinion is considered important and given consideration before key decisions are made.

Conference attendance:American Association of Geographers, Washington DC, April 2019

Documentation: We put documentation of every detail of the project in different kinds of calendars (the grand plan, emails, minutes, files on Dropbox) in a timely and organized manner. We would delegate tasks but not in the area of documentation. After every meeting, we would place minutes and action points. I learnt through experience that the written details were crucial in providing evidence of team participation in making important decisions.

Flexibility: For the Tanzanian team to be productive in writing, it requires flexibility and understanding of the local context that constrains productivity. Different initiatives had to be made, understood and supported financially. I must admit that the consideration of local needs rather than what is strictly planned energized the team and this was very much in connection to the trust that was built in the project.

Learning: There is comfort in being trusted that you have something to offer. When your colleagues make a public announcement that ‘you are the experts, we will learn from you’, this builds confidence in each team member that ‘the project will depend on me in this particular area’. At the same time, this allowed the coordination of different strengths toward producing a particular output. As it happened in the end, every team member’s capacity was improved by careful organization of expertise and activities. That is how everyone’s area of expertise became important for the project’s success. The situation room at CBS is an example of how pulling together expertise to push production of a particular output can increase novelty in a project.

NEPSUS according to Dan (senior member of the research team, now based in Spain)

NEPSUS was conceived in 2014 and discussed early on at a meeting of potential research partners all of whom were attending the ‘Green Economy in the South’ conference held at the University of Dodoma. Then we discussed the modalities of the funders, the possibilities of collaborating with different institutions – who, practically speaking, would be able to manage the finances of a project like this. This steered us towards working with the University of Dar es Salaam as the main collaborator. In January of the next year we all met in Dar es Salaam for a bid writing workshop, planning what we might do and what might be the justification of it. At the same time I was starting a different research project also focused on changing rural lives in Tanzania. The ‘Long-Term Livelihood Change Project’ (henceforth Livelihoods) began in early 2015 with a simple brief: find places which had been visited by researchers in the last 20-30 years; revisit them, preferably with the same researchers, and go back to the same families; see what has changed.

Dan between hard bouts of work: Kilwa, 2017

In many respects the two projects could not have been more different. One post-doc and three main investigators on the Livelihoods Project, a much larger team on NEPSUS. A clear aspiration but no clear programme of execution (Livelihoods), against a clearly designed framework (NEPSUS). Livelihoods was a federated project, researchers signed up to join in, its writing objectives emerged from our findings. NEPSUS was much more structured. And yet there were also commonalities: in output, the main written product in each case a large edited book; in subject matter, we were all investigating change in rural societies; in the flexibility that we learned to foster; and in the policy briefs we prepared.

The existence of cognate projects was one of the advantages that NEPSUS enjoyed. In part this was because we were able to build on the findings of earlier work. Thus our work on asset indices followed the importance of these that the Livelihoods project had emphasized. Similarly we also benefitted from being able to follow and access data that other colleagues had gathered from this very study region, and in some cases, identical villages. Cognate projects also meant that our budget could stretch further. Some aspects of travel and accommodation in one project could cover work in another. My travel to Tanzania could be funded by the Livelihood project if I went there to do that project’s work, leaving only local travel costs incurred by NEPSUS when I turned to that project. Similarly Caleb’s involvement was subsidized by his own, pre-funded sabbatical. Furthermore we were able to leverage other funding opportunities to augment the resources on which NEPSUS could draw. Kelvin’s foundational work in remote sensing interpretation for example was due to our ability to leverage other funds to support a three month stay at the University of Edinburgh from the Global Challenges Research Programme.

We could also learn from and build on things which had gone well in other projects. The media coverage that Christine put together for the book launch of the Livelihoods project was exceptional – and based on that experience it got even better for NEPSUS. The experience of writing the Livelihoods project book (Prosperity in Rural Africa?) convinced both myself and Christine that this would be a good thing to do, and so helped to overcome Stefano’s doubts.But perhaps more than anything else it gave us prior experience of working together. Stefano and Christine were all working on the Livelihood project and conducted fieldwork together on that project with me. We attended writing workshops together in Denmark (because it was the most central point of the federated participants) and in Tanzania. Working together helped us to know and trust each other.

That collaboration was in turn built on earlier interactions and coming to know each other. Christine and I had formed a growing respect for each other’s written work over the previous few years. Stefano and I had interacted over celebrity affairs over roughly the same timescale, and both had known each other as PhD students in Tanzania in the mid-1990s, intersecting at a hostel popular among researchers in Dar es Salaam, where Stefano stayed with his future wife (Lisa) and I met mine (Tecla). Family ties and common networks bound us together. It also helped to forge the ethos of working together that we developed. There was a good deal of conviviality in this project – of cooking, eating and spending time together. The conducive infrastructure of the PhD accommodation at the DFC hostel in Copenhagen and the MS-TCDC center at Usa River in Tanzania facilitated that. But there was also a marked lack of conflict over things like authorship, visibility or funds. The unusual authorship arrangements that distinguishes our edited book (Contested Sustainabilty) are in part a reflection of the freedoms we enjoyed in those writing practices.

This history made some aspects of the institutional aspects of the North-South collaborations that are required for this sort of project easier too. Explaining how universities in any country works (or fail to work) can be exhausting for all sides. The rules, for example, that prohibit the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona from paying for coffee at workshops (just to take one small, but real example) can seem confusing, and the route through or around these restrictions cumbersome. But we began this collaboration with a lot of prior experience that helped us to plan our interactions and project management more effectively.

We similarly had the good fortune to have a great deal of experience of working in these specific study sites to draw upon. Christine Noe had written her PhD in the southeast of the country, around the Selous Game Reserve. So had Baruani Mshale, who unfortunately had to leave the project half-way. Baruani in particular had excellent contacts in villages, districts and regional government as well as with NGOs that made navigating institutional landscapes and officialdom while collecting data much easier, as well as knowing who we needed to talk to when. And sometimes we just got lucky. Anyone who gets to work with Kelvin or Caleb has gotten lucky. This is not just about their collaborative and incredibly hard working approaches to joint projects. It is also about the abilities they brought with respect to computational methods and remote-sensing techniques.

NEPSUS according to Faraja (PhD student at the time of the project, based in Tanzania)

The multidisciplinary nature of NEPSUS was both exciting and intimidating, as it required us to stretch our boundaries, challenge our preconceived notions, and adapt to collaborative thinking.

Flexibility and adaptability: It is not always easy to do things as you planned, sometimes you have to be flexible to changes. One of the most significant advantages of this project was the flexibility it encouraged among its members. The flexibility encouraged me to step out of my comfort zone, learn new skills, and broaden my perspectives. I was flexible to change my former proposal that I developed before the commencement of project and accommodate new perspectives. I also found myself engaging in longer periods of fieldwork, and in data collection and analysis techniques that were completely new to me.

PhD clear task delegation: Although we were working collaboratively, the tasks within the project were divided among different members based on their expertise. The tasks of PhD students were clearly delineated from the beginning and this helped me to make steady progress without feeling overwhelmed. The project leaders encouraged the PhD students to take ownership of our respective areas. This allowed me to focus more on the aspects of the research that aligned with my PhD goals. I also learned that setting milestones and deadlines that needed to be adhered to is important for a successful outcome.

Collaborative data collection: Spending more time in the field helped to uncover a story that at the beginning respondents were not willing to talk about. It helped create more trustful relationships with local key interviewees. I was able to gain hands-on experience in designing and implementing data collection methods that then became invaluable for my development as a researcher.

Collaborative coding of qualitative data: Sitting with a group of researchers together and deciding how to code data together was a new experience for me. Through collaborative coding, we came up with themes that cut across different resources. At the same time, this helped me to apply more uniform and clear interpretations of data from different sites. Such experiences also significantly improved my coding skills and refined my analytical abilities.

Writing workshops and final conference: The project held several meetings in Tanzania and Copenhagen for writing activities. In this meetings, members shared their findings, discussed methodological challenges and provided feedback on each other’s work. These meetings was a platform for me to learn from the group and receive valuable feedback. I also benefited from these meetings as they built collaborative understandings of various concepts and results. Moreover, the PhDs could spend a total of six months in Copenhagen (three for proposal writing and three for finishing the writing of the thesis). This was very important as it offered enough time for us to concentrate on writing.

NEPSUS according to Pilly (PhD student at the time of the project, based in Tanzania)

Despite the complexity of the project design, the boundaries between my PhD work and the NEPSUS project activities were very clear. I contributed to various activities designed for the overall project, such as fieldwork, meetings, writing workshops and dissemination activities but I also had enough time and resources to work on my PhD and complete it on time. The main challenge I faced related to how NEPSUS had selected respondents for household survey, using the head of the household as the unit of analysis. In rural settings in Tanzania, most households are headed by men, therefore there were only a few female-headed households covered in the project survey. Since the focus of my research was on gender I had to add more female-headed households in my study villages to ensure that there is gender representation at the household level.

The three PhDs collaborating and graduating: Dar es Salaam, December 2020 and November 2021

Various joint meetings and writing workshops held in both Tanzania and Denmark played a crucial role in my PhD journey. These workshops provided me with the opportunity to leverage the extensive experience and expertise of the senior project members, as well as to receive invaluable guidance in the writing my thesis and academic papers. Being in the presence of senior members allowed me to present my work and receive timely feedback, a benefit that is often challenging to find in a typical academic environments. Furthermore, the writing workshops fostered an environment for sharing experiences and collaborative learning with fellow PhD candidates. Training sessions organized by the NEPSUS project equipped me with knowledge and skills in various data collection and analysis methods, including Social Network Analysis, and I learned how to analyze qualitative data using Nvivo software. These experiences significantly enriched my capacity to contribute in writing multiple papers and several book chapters for our book Contested Sustainability, an accomplishment of which I am very proud. Participation in both international and local conferences, further bolstered my confidence and improve my presentation skills.

I was fortunate to have the guidance of two academic supervisors, one affiliated with my local institution and the other from Roskilde University, Denmark. This joint supervision enabled me to benefit from their diverse expertise, extensive experience, academic mentorship and practical assistance. However, there were also some discrepancies in the thesis writing guidelines between the two institutions, which initially led to some uncertainty regarding the expectations. Fortunately, my supervisors were able to reach a consensus on the best approach to support my writing process, ultimately contributing to the successful completion of my PhD studies.

NEPSUS according to Lasse and Caleb ( ‘quant situation room’ members, based in Denmark and the USA)

At the project formulation stage, all project members from Copenhagen and the UK travelled to Tanzania for a three-day writing workshop in Dar es Salaam. The aim was to establish team cohesion and to formulate overall research questions, come up with a research design to address them, and assign roles and responsibilities. While the core team was mostly composed of experienced qualitative researchers, it became clear during this workshop that people were interested in expanding the scope of the project to also include quantification of partnership complexity – a central concept for the main research question of the project – and quantitative methods for assessing partnerships’ social and environmental impacts. These ambitions set a clear mark on the comparative research design formulated in the project application and later refined at joint workshops held in Dar es Salaam and Copenhagen during the early stages of the project.

From early on the team was keen on using Social Network Analysis (SNA) to understand the organizational complexity of partnerships, and at the project start a three-day methodology workshop was organized at the University of Dar es Salaam, taught by Lasse who had specialized in the method during his PhD. During this workshop, the team also began developing a protocol for coding up village organizational networks. Lasse worked with all three PhDs linked to each field site during their early fieldwork, visiting villages and developing a common methodology for mapping the village networks. Mapping the evolution of networks is a challenging task, but the team developed a method based on coding up villages’ organizational collaborations historically by: 1) photographing and coding village guestbooks, 2) collecting and coding project documents, and 3) interviewing members of the Village Council and elderly/former members. This provided the team with a set of village partners that could then, in turn, be interviewed to obtain information about mutual collaborations between partners. This data collection and coding played out iteratively, with the PhDs communicating with Lasse regularly and with joint coding sessions both during the Dar es Salaam and Copenhagen workshops (more on this below).

In parallel, with the ambition to engage in quantitative assessments of partnership social and environmental impact, some of the project members toured all 24 study villages to conduct the survey. While the survey was meticulously designed and powered to draw inferences from the village-level respondent sample, it also became clear that assessing environmental impact survey data would at best be challenging, and that temporally and geographically more fine-grained data was needed to establish causal links between partnership evolution and on-the-ground land-use change. Therefore, specialists on remote sensing, Kelvin Kamnde and Caleb Gallemore, were asked to engage in the project. They quickly convinced the team of the usefulness of satellite data to trace developments in land use change after the partnership onset and swiftly became an integral part of the team. In his master’s thesis, Kelvin had worked on validating human-assisted land classification models and his knowledge of how to work with satellite data came to shape the team’s thinking about these issues in the years to come. He also joined the fieldworkers to collect validation data for the land classification models. The geographer Caleb had some experience in land-use modelling and SNA, and helped bridge between team members working with network data, survey data, and satellite images.

During another long-term workshop in Copenhagen, the project participants with primary responsibility for quantitative data analysis worked together in a common room, dubbed comically the ‘quant situation room’, because this team served as a brainstorming group for the quantitative methods to be used to assess the evidence for any causal impacts of the programs the project studied. The situation room brought together project participants with expertise in survey design and data analysis, data visualization, geographic information systems, and remote sensing. In addition to trying to solve the challenging problems involved in assessing evidence of governance mechanisms’ causal impacts, the group also served as a sort of clearinghouse for complex data visualization tasks. Throughout the period of intensive work, project members would drop by for suggestions or assistance assembling more complex data visualizations or identifying appropriate statistical analyses for their individual research questions.

Because several members of the situation room had been directly involved in the research design and data collection fieldwork, they were able to quickly understand the questions and applications that the other project members brought to them, helping to contextualize these questions for the member of the analysis team who was not directly familiar with the fieldwork and was providing support with advanced data analysis and statistical programming. This helped to keep the analysis strategies developed during the work period sufficiently grounded in the overall research objectives so that work on these tasks could continue relatively smoothly after the work period and even over the substantial disruptions resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic.

The opportunity to engage in this kind of intensive discussion and exchange of ideas meant that analytic strategies emerged organically, and, looking back, we would be hard-pressed to say which ideas came from whom. Importantly, the situation room members worked hard to keep the fieldwork experts in the driver’s seat of identifying important questions and relevant local contexts to consider. In this way, the situation room acted as a sort of service unit within the broader project, helping to translate some of the qualitative findings from the fieldwork into quantitative tests that could still be relevant to the local context of the project study areas.

NEPSUS according to Mette (coordinator of NVivo data analysis, based in Denmark)

The key modus operandi for the NEPSUS team was the involvement of all researchers in all phases of the research project from the initial phase of the research design, preparation of data collection instruments (the survey questionnaire, interview guides, focus group protocols, etc.), coordination of fieldwork, data analysis, dissemination of results, and documentation of research findings. A similar approach was replicated during the collection and analysis of qualitative data. It was decided to do the qualitative data coding using NVivo. NVivo is a software which supports the organization, coding and analysis of qualitative data. The researchers that were part of the NEPSUS research project have different disciplinary backgrounds and expertise. This was a great strength but, at the same time, a challenge. Since the NEPSUS project included various sources of quantitative and qualitative data, it can be difficult for all members of the team to understand and benefit from all the data and it can be challenging for researchers to analyze qualitative data if they usually work with quantitative data. We therefore decided to have team workshops where we not only introduced the members to the software, but also organized, coded and analyzed the data together.

The workshops were designed to:

- Attain learning outcomes related to NVivo version 12: focusing on practical skills through learning-by-doing sessions;

- Manage, organize and store qualitative data. The importance of ensuring the quality of the transcripts to be uploaded into the software was highlighted.

- Develop a detailed code book and analytical framework through an interactive process of proposing, revising, and adopting the codes (formulation, revision, adoption).

We decided to organize a one-week workshop in Bagamoyo, Tanzania, located a few hours’ drive from Dar es Salaam, where most of the researchers live. Since we have many other work obligations, it was important to gather everyone in a location far enough from our workplaces so that we would not be disturbed. NEPSUS did not have the option of using NVivo for Teams because of unreliable internet and cost requirements (NVivo for Teams allows participants to work simultaneously on a single NVivo project file on one server). For NEPSUS, we instead worked asynchronously on individual NVivo project files and merged the files into a single project for each sector. Even though it is not an easy task to coordinate a coding process that involves more than ten researchers, it proved significantly useful and after coding, it was much easier for all members to find and use relevant qualitative data.

The workshop also enabled the research teams, with members from different professional backgrounds and with varying research experience and field research orientation, to develop a common understanding of NVivo features and their utility. In addition to organizing our qualitative data and making it more accessible, the coding process provided the researchers with a structure for discussing and analyzing the data together as a group. Another advantage we identified was thus that the preparation process for coding led to important conversations concerning synergies, analysis, definitions and interpretation of data among the team members.

Throughout the coding process, discussions were held to identify areas of agreement and divergence, as well as key themes and patterns. For instance, it was important to be in agreement on the key themes and on how to differentiate closely related codes such as ‘unable to join’ versus ‘uninterested in partnership’. These discussions proved to be beneficial in refining and improving the coding process. Working as a team therefore allowed for the development of a codebook as an analytical framework, which aided in establishing a common understanding of how to conceptualize and interpret the qualitative data.

A central challenge was that NVivo includes several features that can lead to a rather quantitative analysis. This is of course problematic if the qualitative data used has not been collected in a statistically significant manner, but more importantly risks losing the rich material in the qualitative data. It was therefore important to organize an NVivo coding process that ensured an inductive and qualitative approach to the analysis. We used analytical codes, not purely thematic codes. Furthermore, we only coded the sentences that we considered relevant to the analysis. This meant that although every sentence was of course read as part of the coding process, not every sentence was coded. Coding thematically, and coding every sentence, can easily transform the analytical process into a mechanical one. Since coding is not just a process of organizing data, but is also an analytical process, this means that the organization of data will depend on the analytical approach that is adopted. For the researchers involved in coding to establish and work with a common analytical framework, joint preparation was crucial.

The coding process also turned out to be a useful exercise for highlighting the nature of qualitative data and why it is important. Throughout the preparation and the actual coding process, several of the researchers involved emphasized their changed perception of qualitative data. They pointed out that it had become clearer to them why qualitative data is important, how qualitative and quantitative data complement each other and what sort of information can be acquired from qualitative data. Finally, working as a team allowed us to address the coding challenges and develop solutions as a group. Also, through this experience, we came to appreciate the importance of team coding in enhancing the quality of our work and facilitating the processing of large amounts of data within a limited timeframe.

NEPSUS final conference and book launch: November 2021 and April 2023

What have we learned?

Collaborative research projects are always steeped in multiple layers of power inequalities – institutionally, by seniority and different tenure status, by gender and race, by North-South differential access to resources – to name a few. Explicit and collective recognition of these dynamics are the first step in trying to address at least some of the local manifestation of these structural constraints. In the NEPSUS project, we tried to tackle some of these inequalities through a bottom up research design, by setting clear rules, responsibilities and divisions of labour, by facilitating collective fieldwork and publications, and by allowing flexibility, space and time for in-depth engagement. Other elements we could not satisfactorily address, such as those arising from the strictures and diversity of reporting and financial accounting systems, some cases of internal strife, and the provision of appropriate financial and academic incentives for project members who were contracted for shorter periods. Despite valiant attempts at engaging with policy makers and donors, our efforts were best at disseminating our research results (both at the local and national levels) and attracting social and traditional media attention than at actually impacting the design of policies and interventions.

Conviviality, Dar es Salaam, Washington DC and Usa River, 2017-2021

Performance in modern academia is based on the quantification of a narrow range of outputs. From the point of view of publication outputs, we matched and exceeded our expectations – but this is not what made the project special. What made it special was a focus on process – the mutual learning (rather than ‘capacity building’) that occurs best in multi-disciplinary environments, also where quantitative and qualitative skills are collectively appreciated and valorised for what they can and cannot do. Unforeseen circumstances, differences between our understandings of local realities and actual situations, everyday personal health and family situations, and sometimes sheer ignorance on our part meant that flexibility and adaptation were more important than sticking to the masterplan (by the end of the project, version 17 of the masterplan had very little resemblance to version 1). A focus on process also meant learning from mistakes rather than looking away or hiding them. Finally, it means recognizing when enough is enough — we are still sitting on as much unpublished primary material as that we have published.

Some of these challenges do not have to be dealt with only individually or project by project. The design of the research instrument can help navigate them. Having enough funding (DKK 12 million, or €1.6 million, for 5 years for a team of 12-15, including 3 PhDs) was important to avoid deleterious trade-offs, but was not enough to make anyone be in the project just for the extra resources available. Embedded demands that required joint fieldwork and publications (also guided by existing frameworks, such as the Vancouver protocol for co-authoring) also helped to clarify expectations. These did not always work, but most of the time they did. The knowledge that we had the flexibility to extend the project in time at no extra cost (in our case by two years, and it was not because of Covid) meant that we could engage in a ‘more open and slower research process’. Joint workshops and writeshops away from the daily demands of work and family, and the resources to carry these out, made a difference. At the same time, they placed extra burdens on those left behind to tend families. Conviviality added extra value that could not and will not arise from just publishing or posting on social media – cooking, walking, partying together was probably what will remain most strongly in our minds and provide a springboard for possible future collaborations. We need to embed not only flexibility, openness and slowness in research project design, but also conviviality.

Asu: Usa River, August 2019

Dedication

Sadly, while we were working on the final draft of the Contested Sustainability manuscript, our dear colleague and friend Asubisye Mwamfupe passed away. Asu coordinated the forestry work package and the main NEPSUS survey. He was an engine in the ‘quant situation room’ during data analysis. His uncanny ability to reach people in a deep and positive way has left many of us very saddened. He is survived by his wife Helen and son Jonathan. We dedicate this blog post to him. He would have liked it.

Daniel Brockington, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona

Caleb Gallemore, Lafayette College

Lasse Folke Henriksen, Copenhagen Business School

Ruth John, The Open University of Tanzania

Kelvin Kamde, University of Dar es Salaam

Robert Katikiro, University of Dar es Salaam

Rasul Ahmed Minja, University of Dar es Salaam

Faraja Namkesa, University of Dar es Salaam

Christine Noe, University of Dar es Salaam

Mette Olwig, Roskilde University

Stefano Ponte, Copenhagen Business School

Pilly Silvano, University of Dar es Salaam

Photo credits: NEPSUS project