by Ayelech T. Melese and Lindsay Whitfield

Industrialization is the main driver of higher per capita incomes and a rising standard of living in low-income countries. Industrialization may be catalyzed by foreign direct investment. However, it is sustained by national firms becoming internationally competitive in range of industries, which should increase in technological complexity as firms building their technological and organizational capabilities.

In contemporary global production and trade systems, locally owned firms in low-income countries find themselves in an increasingly difficult situation. They have limited existing knowledge of the industry and thus face a large gap in the capabilities they have and those that are required to be internationally competitive. Over the past decades, the barriers to entry in even basic manufacturing and agriculture-based export industries have increased. These barriers to entry include stringent and fast changing requirements by Western buyers, strict proprietary rights, and stiff global competition from suppliers in other low and middle-income countries. Locally owned firms must build their capabilities but face big risks in doing so as they often have scarce financial resources, weak international networks, and operate in precarious business and political environments.

In such a context, one would wonder what can motivate local firms to enter an export industry new to their country, invest in learning, and succeed in build their technological capabilities. Seeking to answer these questions, we examined the locally owned firms in Ethiopian floriculture export industry which emerged in the 1990s, following the coming of a new government into power and the subsequent policy shift from command to mixed economy. Local firms must master significant technological and organizational skills to run a cut-flower firm, which is more like manufacturing than agriculture.

Drawing extensively on the historical evidence, scholars of industrialization in East Asia emphasized that industrial policy has been the key driver of private investment and firm level learning. This literature significantly contributed in highlighting what the industrial policies should look like and how they should be customized to the twenty-first century’s context to achieve similar effect in low income countries in Africa and elsewhere. Notwithstanding the important contributions, the industrial policy literature has given limited attention to firm-level dynamics of learning and agency of firms in (re)allocating resources based on their own business strategies.

Our examination of the Ethiopia’s floriculture export sector largely confirms the arguments of industrial policy scholars. The sector went through exponential growth during the period 2002 to 2008. This growth was driven by sector specific industrial policies that provided generous incentive packages and infrastructural support that spurred both local and foreign investment, but notably significantly lowered the entry barriers and risks for local investors as they sought to build the required capabilities.

However, the sector did not keep the momentum of growth and technological upgrading for long. In the 2010s, as growth in the sector stagnated, the number of local firms declined significantly. Only fifteen local firms managed to survive and thrive, most which were part of family-owned diversified business groups. Our analysis shows that the local owners of cut-flower farms often sought to develop only the minimum capabilities needed to sustain their cut-flower exports. Government industrial policies which incentivized local entrepreneurs to invest in the sector did not entail performance standards that tied the financing and other support to export performance and thus firms had little incentive to continue to invest in learning.

Scholars of global value chains (GVC) discussed the important role and potentials of GVC configurations to bolster learning and upgrading opportunities of local firms in low-income firms. Upgrading is often confined to a certain level as local supplier firms encounter various control mechanisms exercised by lead firms in the GVC. However, local firms can exercise their agency with a much broader scope that is often (implicitly) assumed. The case of Ethiopia’s cut-flower export industry shows that local firms can pursue growth paths within and across GVCs, as they are part of diversified business groups and firm owners make decisions not only about the growth of the cut-flower firm but also about the overall profitability of their business group.

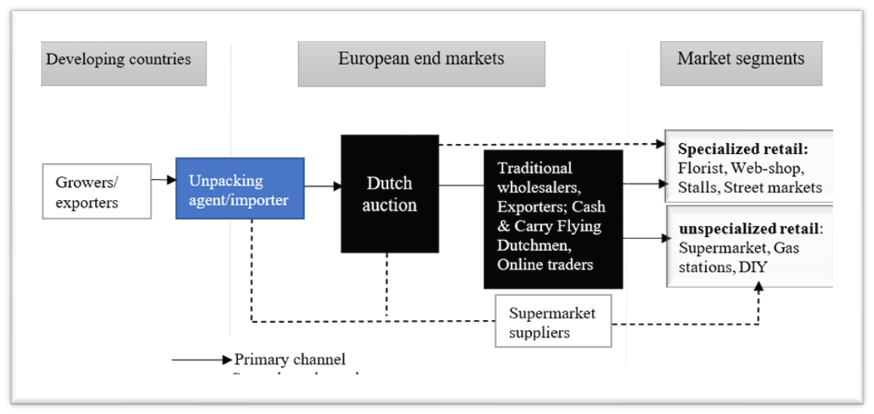

The mapping of the floriculture GVC below shows that flowers are traded in the Dutch auction, which remains the dominant channel, and through direct sales to wholesalers, supermarkets, and other retailers, which has become more important since the 1990s. The specification of buyers in the direct sales channel depends on their end-markets and market segments. Consumers with special demands often buy flowers from specialized outlets such as florists and web-shops.

By the time Ethiopia joined the global cut-flower industry, the abundant year-long supply was causing stiff competition and putting downward pressure on suppliers’ profit margins. Non-price competition such as reliability and consistency in terms of product quality, quantity and delivery was becoming more important. As a result, buyers’ requirements became more stringent to differentiate products, but also address growing consumer and non-governmental organizations’ concerns about labour and environmental issues on flower farms.

Ethiopia’s national firms chose various export trajectories combining different market channels and end-markets, while protecting or improving the overall profitability of their family-owned diversified business groups. These export trajectories dictated which capabilities they needed to build and to which level to keep their flower export firm internationally competitive and thus retain buyers.

In this context, owners’ decisions for their cut-flower firms and their growth paths were influenced by the limited resources of their diversified business groups and showed significant variations. Firm owners sometimes chose to invest less in building the capabilities of their flower export firms to release resources and managerial talents to other affiliate businesses or make investments in new domestic market industries. On the other hand, some family business groups transferred resources from their domestic market-focused firms to subsidize the costs of building capabilities in their flower export firms.

The analysis also shows how the higher organizational and managerial demands of operating a firm in a competitive export industry like floriculture precipitated a move toward modern management practices in this first generation of family business groups in Ethiopia. These findings emphasize the need to consider local firms’ capabilities and position with family business groups when designing industrial policy.

Read more in our recently published article:

Industrial policy, local firm growth paths, and capability building in low-income countries: lessons from Ethiopia’s floriculture export sector, Industrial and Corporate Change, advanced access.