How can an entire industry flourish during a crisis, yet plunge its workers into precarity?

As Sri Lanka is battling its worst economic crisis for 70 years, this blog looks at the crisis’s paradoxical effects on the firms and workers in the Sri Lankan apparel industry.

Sri Lanka: economic crisis and the apparel industry

Sri Lanka is currently battling with what is being described as the worst economic crisis since the country’s independence in 1948. In March 2022, Sri Lanka declared itself bankrupt, having defaulted its foreign debts of over $55bn. Without adequate foreign reserves, the government has been struggling for over a year now to provide its citizens with the most basic needs such as fuel, electricity, gas, essential drugs, and foods. The food security is severely threatened by the ongoing fertilizer problem in the country which has destroyed and slowed the growth of crops including rice, vegetables, and fruits.

Against this turbulent economic backdrop, the fate of the apparel industry has been a major concern. The apparel industry is the most significant contributor to the economy, accounting for over 45% of the country’s export earnings. Media, researchers, and industry stakeholders predicted and continue to express their concern that the country’s economic turmoil and political instability could adversely affect apparel exports. On the one hand, stakeholders were concerned that the lack of steady supply of fuel and electricity would affect the smooth operations of the industry. On the other, it was noted that brands and retailers have started to move sourcing orders from Sri Lanka to neighboring countries to mitigate the risks. As JustStyle reported in mid-2022, some of the expected consequences were loss of business and revenue and re-location of production to other countries. Furthermore, given that Sri Lanka’s apparel production relies on imported raw material, an increased concern was the ability of Sri Lankan manufacturers to afford the foreign currency reserves required to purchase raw material to fulfil orders.

Winners and losers: the remarkable performance of the apparel industry

As the crisis evolved through 2022 to 2023, contrary to these initial concerns, the apparel industry has been performing surprisingly well. A closer look at the crisis response reveals that the industry is cushioned by concessions granted by the government and advantages of foreign trade that are not available to local businesses. Power cuts, at times extended to 10-13 hours per day, did not apply to export processing zones and the garment factories located in other areas. Recognising the importance of export production, the government excluded the locations of garment factories in their electricity demand management schedule. Similarly, even though there has been a severe shortage of fuel – with fuel stations shut down for weeks – the apparel industry saw a steady supply of fuel. As quoted by a key apparel manufacturer “I think as an industry we have been fairly insulated throughout the crisis because there was a recognition that the only way out of the crisis is to focus on apparel and tourism. So, there were certain changes made by the government that allowed us to source raw material and operate factories without any interruptions”. In addition, with the US Dollar value going up 100% against the Sri Lankan rupee overnight in March 2022, the industry gained significantly from the exchange rate depreciation, especially since the workers’ salaries and some production costs remained unchanged. Furthermore, manufacturers have been able to keep some of the revenue in offshore accounts, a practice currently being debated and criticised by media and activists.

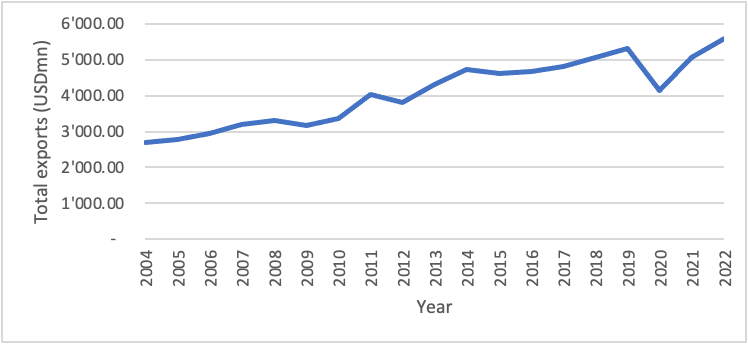

Despite the ongoing political and economic turbulence in the market, investors have continued to show interest in the sector. The Board of Investment Sri Lanka reported that it has signed agreements worth $76m for new investments and expansions in the sector in 2022. The industry’s remarkable resilience against the economic challenges were shown with an all-time high revenue of exports in 2022. As per the Joint Apparel Association Forum, June 2022 recorded the highest performance for a month ever reported in the industry, with a 39.45% growth of export revenue. By December 2022, Sri Lanka reported $5.6bn revenue from apparel exports, a 10% increase from 2021 and a 5.6% increase from 2019, the pre-pandemic context. Thus, contrary to the mainstream opinion that the economic crisis would set-back the apparel industry, the industry has shown not only resilience but a significant growth.

Growth of exports revenue in the Sri Lankan apparel industry: 2004 – 2022

Winners and losers: where are the workers?

The resilience of the capitalist economic system is such that even against unprecedented disruptions, capitalists emerge as stronger than ever. The moment a crisis strikes, the foremost concern of nation states and capitalists is the resilience and recovery of business. To this end, governments prioritise the needs and wants of businesses, with greater concessions granted to business owners to deal with the crisis. Existing strategies are strengthened, new strategies are drawn, and new plans are made. Yet, this latest example of the Sri Lankan economic crisis shows that workers who are toiling at the bottom end of the businesses are left behind.

While the apparel industry has grown from strength to strength, apparel workers are being pushed to further precarity. As a manufacturer himself admitted, “the real people who felt the crunch of the economic crisis are workers”. Since March 2022, living costs have increased at an unprecedented rate, with prices of essential goods going up by 400%. In contrast, existing standards of the industry are eroded, with workers having to deal with loss of financial and material benefits such as overtime, bonuses, increments, transport, and free or subsidized meals. This has left over 350,000 apparel workers who were already living on subsistence income struggling to survive with their monthly salary. Their salary falls between $45 – $90, with $45 being the minimum wages in the industry and $90 being the total take home salary including overtime and production incentives that are available for workers. With salaries remaining the same and some of the incentives removed, apparel workers are struggling to fulfil even their basic needs. Even though a monthly Emergency Relief Allowance (ERA) around $27 for workers has been established to counter the effects of currency devaluation and skyrocketing inflation on workers’ livelihoods, the Clean Clothes Campaign found that apparel workers have not been receiving the full ERA. With the absence of any support mechanisms, local civil society organisations in the Katunayake Export Processing Zone revealed that they are currently running soup kitchens every weekend to provide meals for the most vulnerable segments of workers such as pregnant and lactating mothers. How does one reconcile this paradox: while the industry is thriving, its workers are starving?

Images of soup kitchen operated by Dabindu Collective, Katunayake Free Trade Zone

Making sense of the paradox that does not make sense…

Externalising the costs of business has been the modus operandi of capitalists, where these costs are often born by the society and environment at large. In this vein, has the resilience and recovery of the Sri Lankan apparel industry been achieved partly at the cost of the financial, material, and emotional wellbeing of workers? Do the apparel workers lives matter less? These workers, integral to the Sri Lankan economy, are largely part of the hidden workforce of global supply chains and already face poverty wages and very few if no social protections. The economic and social disruption of crises – both the Covid19 pandemic and the economic crisis – have threatened the long-term livelihoods and wellbeing of hundreds of thousands of Sri Lankan apparel workers, predominantly women and primary caregivers in their families.

In an industry where ethical sourcing is supposedly playing a central role, how ethical is it to leave the workers behind in the capitalist agendas of resilience and recovery? As the Clean Clothes Campaign (CCC) revealed in early 2023, many attempts to engage with brands urging them to take actions to safeguard the livelihoods of their workers have been futile so far, except for ASOS, Patagonia, and Victoria’s Secret who have reacted positively. Throughout the year of the crisis, CCC has been calling upon brands to ensure that the workers in their Sri Lankan supply chains are paid the ERA unconditionally while securing workers right to organise. As a trade union quoted, “Sri Lankan garment workers have contributed to making these brands rich. Therefore, the least these brands can do is to ensure their workers get through the crisis”. The story of Sri Lankan apparel workers in crisis has laid bare the systemic failure of brands’ ethical codes. Ethical codes have barely been able to protect apparel workers at the best of times, but they have been little to no use when the crisis struck. Brands can no longer continue to pretend that their regulatory interventions are working on the grounds. This leaves us with an important question. How can decent work really be ensured in global supply chains? Who should and can take the responsibility to protect workers’ interests? Where do we go from this point?

Operation in crisis mode now seems to be the ‘new normal’ for global supply chains. For Sri Lanka, economists predict that it will take at least ten years to reverse the effects of the crisis. Precisely because of this, the Sri Lankan apparel industry is in urgent need of an inclusive, just, and equitable plan that will ensure not just the resilience and the growth of the industry, but also the material and emotional wellbeing of its workers. If a commitment to such a plan is not forthcoming from brands and manufacturers, then it is the responsibility of the government to safeguard the rights of workers.

If the government is also not capable of stepping up to do what it should have been doing in the first place, then the only realistic solution is a collective intervention delivered through a multi-stakeholder initiative. Such an approach can be similar to the Bangladeshi Accord (the Accord on Fire and Building Safety), with legal teeth to hold brands and manufacturers responsible for living wages and fair working conditions in the industry. A focused and targeted intervention like this can only be driven at the global scale by workers representatives, where enforcement is grounded on a chain of market sanctions, seeking first to influence consumer decisions and apply pressure on brands, with the brands transferring this pressure to manufacturers through their purchasing decisions. Like in the case of the Accord, such a collective effort may have the potential to protect workers interests and ensure that workers are not left behind. It will help workers cope as the economic crisis and the resultant inflation escalate at an unprecedented rate in the country, creating havoc on their lives and livelihoods for years to come.

Shyamain Wickramasingha is a Research Fellow at the University of Sussex Business School, and a Visiting Fellow at CBDS, within the Department of Management, Society and Communication at Copenhagen Business School. Her work focuses on the political economy of global production networks with an emphasis on inter-firm relations, uneven development, and labour regimes.

Additional resources on the Sri Lankan apparel export industry by the author:

- CBDS Podcast: Informality in the Sri Lankan apparel industry – choice or no choice? CBDS Podcasts with Prof. Lindsay Whitfield and Dr. Shyamain Wickramasingha (Episode 2).

- Wickramasingha, S. (2023). Re-imagining vulnerabilities: The Covid-19 pandemic and informalised migrant apparel workers in Sri Lanka. Research Paper, International Center for Ethnic Studies, Colombo.

- Wickramasingha, S., & De Neve, G. (2022). The collective working body: Rethinking apparel workers’ health and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic in Sri Lanka. Global Labour Journal, 13(3).

- Wickramasingha, S. (2022). ‘Living for the day’: Informality, gender, and precarious work in the Sri Lankan apparel industry. SSA Polity.