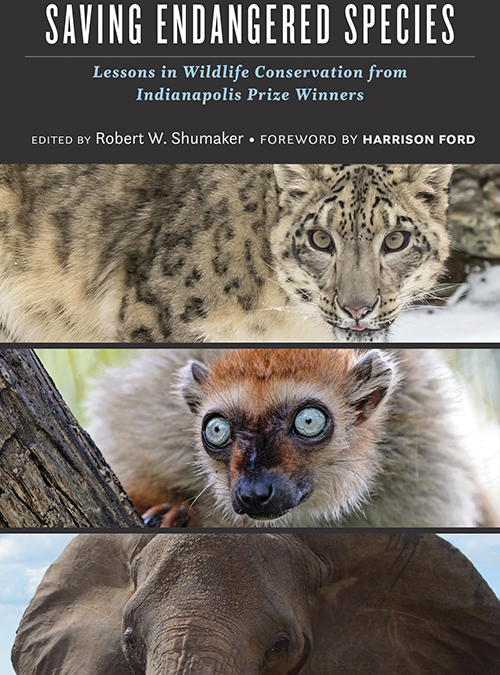

Book Review of Saving Endangered Species: Lessons in Wildlife Conservation from Indianapolis Prize Winners.

This book review has first been published by Conservation and Society.

And yet, for all its beauty, this book could have been titled, ‘White People and the Animals they Love.’ I start with my fundamental critique because for some readers, this will be all they need to hear to check this book off their ‘must read’ list. These readers, however, will be hard pressed to find other works of conservation biography that aren’t also easily critiqued for their class, racial, gender, and geographical elitism.

Also, a disclaimer, I am a social scientist who works in some of the policy spaces, ‘partnership’ imaginaries of business and helping, and geographical areas covered in this book. Thus, I am among the ‘to be inspired’ of the intended audience for this book. Additionally, the introduction, written by Dr. Robert W. Shumaker (evolutionary biologist, president and CEO of the Indianapolis Zoo) calls for ‘a more integrative approach in which the centrality of humans is recognized in the conservation agenda’ (p. 6). Thus, a review by a scholar of humans might be reasonably appropriate.

In spite of the fact that the index does not include the term ‘celebrity,’ the book epitomizes what has come to be called ‘celebrity environmentalism’ (see Abidin, et.al 2020). The practice of scientists, film stars and social media influencers among others, who ‘enjoy public recognition, publicly support environmental causes, and benefits from their sustained public appearances’ as celebrity environmentalism may be a way of bringing new resources to conservation.

The celebritized approach to conservation is clear from the Introduction’s start. While the reader might expect the star of this chapter to be the American Bison, named the official mammal of the United States in 2016, and depicted as a steadfast and grandiose being in the illustration that precedes the text, it is not. The star is the celebrity conservationist William T. Hornaday who initiated the first-ever zoo-based conservation effort as a result of his initial desire to provide a live bison model for better taxidermy (p.2). Thus, the scientific model for which the book collects a series of testimonies, is linked to the efforts of Hornaday. He was the director of the Bronx Zoo in 1906 when Ota Benga, a Mbuti man from Congo, was displayed in a cage in the monkey house. Hornaday wrote to the New York city mayor that ’When the history of the Zoological Park is written, this incident will form its most amusing passage.’ Many people at that time, such as the Black clergyman Rev. James H. Gordon, were not amused. Many readers today will question the unambiguous celebration of these violent and dehumanizing roots of a movement intended to provide a moral approach to saving nature.

Distinctions are signaled between the scientific authors and the celebrity environmentalists through engraving the masthead of every other page with a ‘Dr.’ before the scientists, with other names presented title-less. Yet, these contributors are all performing the limited scripts of celebrity environmentalism: notably contributions enact specific tropes outlined by Abidin and her colleagues. We see contributions from the ‘Ambassador’ trope of high-profile performers who are patrons of NGOs and foundations, but whose personal commitment varies between superficial co-branding and long-term engagement. Quite prevalent is the ‘White Savior’ trope in which ‘wild places’ need to be saved from ‘locals’ through the actions of white people. The book also highlights the ‘Activist Intellectual’ trope promoting cerebral and scientific reasons to support conservation, that then become celebritized through a focus on funding, media and elite networking. Finally, the book’s promotional writing enacts the trope of the environmental ‘Entrepreneur’ where conservation is meant to provide a good investment for business-minded people.

The book opens with a long vignette from Harrison Ford at the 2018 Gala celebration referring to his co-contributors and others like them: ‘You can call them researchers or scientists or conservationists. But let’s call them what they really are: These are heroes. Real heroes.’ (p. 17). However, as this book shows, the heroic narrative structure makes forging alliances and political solidarity across lines of class, race, cultures and politics quite challenging. Heroes stand above others, they are exceptional. And, as such, conservation through heroism is unsatisfactory, if not oxymoronic. Conservation and the environmental politics that can sustain life on our planet call for less singularity, fewer stories of individuals excelling over other people and nature, and more connectedness, cooperation and coexistence.

The introduction tells us that ‘these are the voices of the greatest conservationists of our time’ (p. 17). I have no reason to doubt that these are their voices and that they are great conservationists, whatever criteria make up ‘greatness’. The stories are full of passion and genuine concern for conservation, so there is no doubt that these heroes are acting from noble intentions. However, the heroic hubris prevents the reflection over either why chickens when pushed off a roof don’t ‘progress well in flight’ (p. 21) or why ‘with no prior thought’ wildlife conservation should be best achieved through ‘a big cash award’ and an ‘exciting and glamourous event’ (p. 305). With some notable exceptions, this book presents the same old stories of great men who just happen to have no reproductive obligations (with the predictable exception of the female scientist), so they can go singularly or with the support of a doting wife into long-term relationships with animals. These men also have friends with lots of money and political clout, and the documentation of elite networking practices that comes through in the chapters actually works counter to a singular hero at the helm of conservation. Finally, these conservation heroes rely heavily on a competent staff of Black and Brown people who can put lofty ideals into practice, while not usurping the limelight from celebrity environmentalists.

Some of the more ‘Activist Intellectual’ celebrity environmentalists present compelling arguments in lively texts around global warming and the contentious politics of saving the polar bears. Many of them take the reader through a combination of wildlife daily habits, international fundraising, and management of research and training projects. These are narrated as a partial life-history of a single ‘hero,’ and while there are nods to ‘local supporters,’ ‘scouts’ and collaborations between ‘enthusiastic’ local staff and international volunteers, this book tells a dangerous single story. It’s time to remind ourselves and our peers that the heroic narrative of celebrity conservation may be useful for raising funds from businesses and for garnering the attention of bored bureaucrats, but it has dangerous political consequences. A close reading of the text finds examples such as four ‘community game scouts,’ the ‘local African supporters’ in Kabara, and the ‘young Samburu warrior’ who was ‘walking in the bush’ with David Quammen, a writer from National Geographic (p.80). Samburu people have proper names, no less notable than people from Cincinnati, and the young man was not working as a warrior when assisting on a conservation project. These people are being rendered mundane through the repetitive text of the white savior narrative. They are being de-humanized as they remain in the background of the African or Asian ‘habitat’ for animals. The heroic narrative is based on an ongoing history of inequality between races, classes, genders and cultures.

The afterword, written by the CEO of the Indianapolis Zoological Society (2002-2019) reads like advertising copy for ‘Western Civilization’ complete with God, Guns and Gold. It is a colonial vision of men like Paul Erlich in which the ‘dangers of unchecked human population’ are called out as problems while fossil fuel addiction, or all those flights to the Galas celebrating conservation heroes, are left unmentioned. The ‘Danger of a Single Story’ by Chimamanda Adichie taught an important lesson in 2009: ’The single story creates stereotypes, and the problem with stereotypes is not that they are untrue, but that they are incomplete.’ This is a beautiful book in its intentions and its aesthetics; the stories are often compelling and transport us into the lives of cranes and elephants and into some of the world’s most notable conservation initiatives. Yet, despite its intentions, the people are missing from this heroic script of celebrity environmentalism.

Perhaps these people are left-out by design. Dr. George B. Schaller writes clearly: ’My account here demonstrates that conservation is not part of development’ (p. 78). But, conservation is part of development. It is impossible to define conservation otherwise (Adams 2004). Both conservation and development are part of the holistic process of living sustainably on our planet. This book is intended to celebrate ’people as a primary factor in conservation.’ We do learn a lot about a particular sub-group of privileged people, their psychology and insecurities, their dreams and aspirations, about networks of elites across the globe who happen to have farms, foundations or PhD scholarships to spare. But we learn far less about the non-celebrity people in the lives of animals. Surely a global conservation movement that manifests the holistic visions and ’the connectedness of all living things’ (p. 119) that many of these contributions also embrace, needs less heroism and single stories and more solidarity, comradery and complexity.

References

Abidin, C., Brockington, D., Goodman, M. K., Mostafanezhad, M. and Richey, L. A. (2020) “The tropes of celebrity environmentalism.” Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 45 (1): 1-24

Adichie, C. (2009) “The Danger of a Single Story” TED Talk https://www.ted.com/talks/chimamanda_ngozi_adichie_the_danger_of_a_single_story

Adams, W.M. (2004) Against Extinction. The Story of Conservation. Earthscan, London.