By Lisa Ann Richey

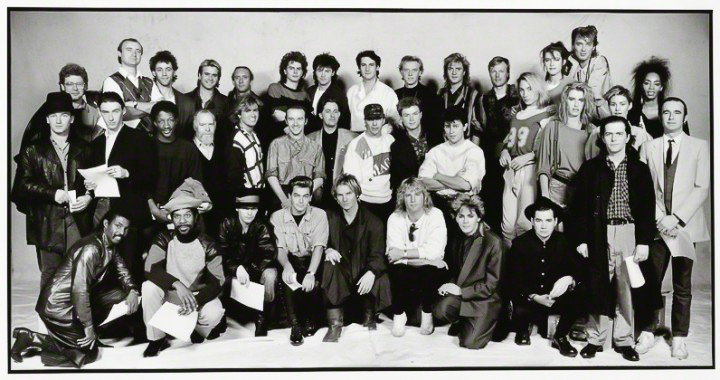

This year’s anniversary remake of Band Aid’s ‘Do They Know It’s Christmas?’ was unveiled amid renewed discussion about the song’s portrayal of Africa.

For 40 years now, Ethiopians specifically, and Africans in general, have been doing the work of being worthy recipients for band aid. Now, they should be recognized for that work and rewarded as workers. As I have argued here, Africa has become a market for profiting from Whiteness. Thus, the reasonable response to fulfill all those generous Christmas-inspired longings, is to pay Africans for their work.

Like the ghost of Christmas past, the tedious melody of white saviourism/effective emergency fundraising (pick your lens) hit the playlist in December, and we returned to tired debates over whether disempowering stereotypes of suffering strangers are OK, if they result in the means to reduce their pain. Sir Bob Geldof summed up his defense of the jingle saying: “There are 600 million hungry people in the world – 300 million are in Africa. We wish it were other but it is not. We can help some of them. That’s what we will continue to do.”

Actually, Bob, there are other ways of understanding the problem of global hunger and of working towards its solution. But your framing of the ‘problem,’ echoing prevalent understandings that African suffering results from a combination of ‘natural’ disasters and local malevolence and mismanagement, all of which are delinked from global production chains and capitalism’s victors, serves elite interests, not hungry people.

My argument is based on my commodifying compassion collaborative research project that explains how producing the good feelings for helpers is a form of affective labor. Causes have been treated as commodities, and sold by celebrities like Geldof for decades. Simultaneously, scholars have critiqued the legacy of ‘band aid’: consumer humanitarianism, ‘brand aid’ and celebrity activism are examples of the corporate norms infiltrating humanitarianism and development.

Moral responsibility, the currency peddled by Geldof, is based on pity for the Ethiopians suffering from famine, not on demands for justice. While pity played a role in charity-based philanthropy historically, the marketability of the feelings of compassion—actually selling these feelings for profit, whether the proceeds go to a celebrity or other private business or to a non-governmental organization, is a recent trend in contemporary neoliberal capitalism. Today, when ‘band aid’ is again revived to try to reinvigorate the attention economy for aging superstars, Ethiopian spokespeople are working to educate Northern publics on the absurdity of these well-intentioned interventions that sent cake and gold to unwitting strangers at the cost of defining an entire nation as pitiful, suffering and lacking.

If we consider that work that produces something of value, understood as something that can be sold for a profit, should be paid. Following this argument, the money made from six iterations of Band Aid singles, including celebrity appearances, merch, donations to charities, and of course, the record itself, should be considered as profit. Geldof estimated that they had raised more than 200 million GBP and issued a statement confirming that ‘100% of all publishing revenues from the sale of the song over the past 35 years (and continuing) and amounting to tens of millions of pounds go and have gone directly to the Band Aid Trust for distribution to projects that aim to help the poor in several countries in Africa.’ In harsh retort to accusations on Twitter that Geldof and Midge Ure had themselves profited from Band Aid over the years, a media push defended the philanthropic model. As summed up on James O’Brien’s morning call-in talk show on LBC Britain’s first licensed commercial radio station, ‘To be perfectly clear neither Midge nor Bob have ever received a single penny in royalty revenues from the song or any activity whatsoever regarding Band Aid including the Live Aid and Live8 concerts or the 4 separate versions of Do They Know Its Christmas?’

Yet, framing the problem as whether or not the celebrities directly profit is a red herring to distract the public from more deeply critical considerations of why claiming to help Africans can produce a profit to begin with. Why are recipients of Band Aid considered to be just that— passive takers of the goodwill of compassionate people in the places where Christmas is the chance to claim our moral worth? Because there are profits to be made from worthy helping. Global ‘helping’ initiatives like Band Aid should be held to the same standards as global corporations. Businesses must balance payments between their inputs and labor. Then after balancing inputs and outputs to reveal profit, they are required to distribute dividends with all of their shareholders. Ethiopians should be seen not as recipients of help but as agents, working as part the production cycle for feelings of beneficence. These sentiments, emotions and feelings are used to sell stuff.

Instead of worrying only about whether the profits are going to celebrity humanitarians themselves, we should instead recognize that the recipients of all the global do-gooding are providing their labor in the production of our good feelings. Thus, they should be paid for this work.

Note: This blog post first appeared on the LSE blog, which can be found here.

Photo credit: Wes Candela used with permission CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

Lisa Ann Richey, Professor of Globalization, Department of Management, Society and Communication, Copenhagen Business School